When visitors to the Jacksonville (Fla.) Zoo’s new Range of the Jaguar exhibit see what appears to be a 400--year--old Mayan ruin, they probably don’t realize that almost everything they’re looking at is made of concrete.

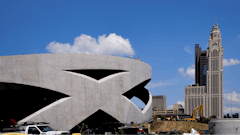

Built as part of a zoo master plan originally conceived in 1992, the $15.4 million 4.5 acre exhibit, which opened in March after 18 months of construction, houses about 100 different species of animals, including four jaguars.

There are four main public buildings in the exhibit: the Lost Temple, the aviary, the jaguar enclosure, and the cafe and market. Different concrete techniques were used depending on the needs of each facility as well as environmental and budgetary considerations.

Why concrete?

Concrete is considered an ideal material for constructing zoos. It is durable, easy to clean and able to take on almost any shape or color. “We build hospital--quality facilities outdoors,” director of biological programs Karl Kranz explains. “The concrete work needed to be well done in order to meet our caging tolerances, where we ask that the floors be roughened so that animals will have good traction. It needed to be smoother in pools so when they go swimming, they don’t hit something rough on the side of the pool and damage their skin. We really like the drains to be at the lowest point of the floor.” This allows the floors to gravity drain without puddles, but is not easy to achieve.

Concrete was also used extensively in nonpublic areas. “In terms of long--term maintenance and wear, concrete is the most durable and cost--effective product that could be used,” notes Steve Wetherell, director of project development for general contractor, The Stellar Group. “The use of concrete slabs in behind--the--scenes spaces, keeper areas and animal holding areas permits a greater level of sanitation, and its use in public spaces allows flexibility in finish and appearance. Concrete was used to construct and create the illusion of mud paths, trees, stone, wood decking and wood timbers.”

An environmental issue

The zoo is within 750 ft. of a bald eagle nest. Because these birds are a threatened species protected under federal law, they cannot be disturbed during their breeding season. As a result, Stellar suggested building the Lost Temple – which houses the reptile, amphibian and fish collections – using tilt--up concrete panels. “One reason we decided to go with tilt--up is because the building could be put up very quickly so it would be up before the eagles came back for the nesting season,” Kranz says. “We had to prepare a month--by--month book for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to tell them what we were going to do. We even had to change access points for the concrete trucks depending on where we were in the nesting season. We were allowed to work inside the building after the eagles returned. It was quite a challenge to meet the deadlines and budgets without disturbing the eagles.” Some work was done out of the normal sequence in order to meet deadlines while accommodating the eagles, notes Wetherell. Breeding was unaffected, with the eagle pair raising two chicks during both nesting seasons while construction was underway.

Using tilt--up had other benefits. “This approach allowed wall fabrication to occur on the opposite side of the temple building footprint from the eagle nest site, outside the zone of influence,” says Wetherell. “Manpower, formwork and equipment in the areas adjacent to the nest were very limited with tilt--up as opposed to erecting scaffold for masonry or large formwork sections for cast--in--place concrete, and having material lay down occur at multiple locations around the building.” This meant quicker completion of the work and reduced construction cost.

Decoration courtesy of concrete

In decorating the 4,000--sq.--ft. Lost Temple, Cemrock Landscape, Inc., of Tucson, Ariz., did research so the sculptures and carvings would realistically portray the Mayan influence. The building’s interior contains walk--through exhibit areas including nine water filled pools.

“The challenge of these exhibits is trying to put realism in them and to make the shapes that we build out of concrete look like different stratas of rock, large standing trees, structural tree trunks, fallen tree branches, carved temple blocks or big boulders,” Cemrock Project Superintendent Larry Hansen explains.

The concrete visible on the temple walls was carved by hand using a variety of hand tools, even specialized ones the carvers developed themselves. “When you apply the texture coat, which is basically a plaster coat, you trowel it up to shape it a bit,” Hansen says. “The coating thickness varies from 2 to 4 in., so you might rearrange it with regular trowels. Then you use a knife or tuck pointer or margin trowel or a specially designed tool to achieve the final design.”

Another decorative concrete feature in the temple is a “tree limb” that looks like it fell through a hole in the roof. There are little pockets in the concrete with bromeliads planted inside them. “These plants don’t take any nutrition from the trees they normally live on,” Kranz explains. “They catch water with their leaves and other animals deposit wastes or die in the pockets, providing them with nutrition.” This means they can live as well on a concrete tree as they would a real one.

The 20,000 sq. ft. of visitor walking paths have integral color made to look like mud. Impressions of leaves, jaguar footprints and white--tailed deer tracks are permanently imbedded in these paths. This decoration has no effect on their longevity. “The load placed on the paths is pedestrian traffic, and the indentations do not markedly reduce the cross sectional area of the slabs,” Wetherell says.

The 6,500--sq.--ft. cafe and 2,600--sq.--ft. restroom building were made of concrete block with the walls decorated using stucco to simulate deteriorating plastered adobe blocks. Because their exterior walls and individual interior spaces are smaller than the temple, using tilt--up would have been more expensive, Wetherell says. These buildings also did not have the heavy concrete facades of the temple, so they did not have to support additional loads.

The 35--ft.--high, 100--ft.--diameter aviary is supported by what appears to be a giant tree. It, too, is concrete, with the tree concealing internal steel support beams. The tree also contains nest boxes and planters, so an irrigation system and service access hide within it. Hansen suggests that the steel pole may not have been necessary. “The tree we built around the column may have been able to support the center of the structure on its own,” he says.

Two jaguar enclosures totaling nearly 10,000 sq. ft. with the capacity for 12 jaguars were made of poured--in--place concrete, hand--carved and theme--painted concrete, masonry and timber framing and scaffold. Through impact--resistant windows inside the cafe, visitors can observe one enclosure, viewing waterfalls, both natural and carved concrete sunning logs, stone ruins with dense foliage and underwater pools. Other exhibit areas house mammals, otters and primates.

Simulated ceramic tile behind the fountains, floor tiles, more than 40 statues, stalactites and stalagmites in the bat enclosure, and “wood” beams over the large windows in the viewing areas were also made of concrete. A cast concrete bench and more than 30 stellas made to look like Mayan stone were fabricated at Cemrock’s Tucson facilities and shipped in by truck.

Working in public

While working at a public facility like a zoo, contractors need to be aware of their audience. “We’re not your average client,” Kranz points out. “We have a lot of demands and expectations. We’re open to the public all the time and they even enjoy watching the contractors working. It’s a real educational process for contractors who haven’t worked at the zoo to be mindful there’s a public there and how to be around animals.”

The zoo’s expectations for the project were well satisfied. “The contractors cared about this project more than any I’ve ever worked on before, all the way down to the guy with the trowel making the sidewalk,” Kranz says. “I feel like we really received a quality job.”