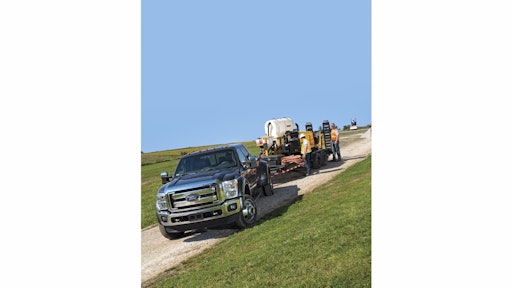

Today’s heavy-duty diesel pickups and chassis cabs pump out in excess of 800 lbs.-ft. of torque and are capable of towing trailers up to 31,200 lbs. That is a dramatic increase in capability over the past decade. If we single out the “1-ton” pickups, there has been up to an 83% increase in rated towing capacity over the past 10 years. Other heavy-duty pickup and chassis cab segments have seen similar steep growth curves.

This increase deserves careful consideration when purchasing your next trucks. You may be able to gain efficiencies by carefully matching your needs to the individual truck’s capabilities, whether that means downsizing the truck to gain efficiency or upsizing to replace your previous, larger towing rigs.

“If you look where heavy-duty pickups came from, the growth curve has been pretty steep,” says Dennis Slevin, vehicle engineering manager for Super Duty at Ford Motor Co. Will this trend continue? “I don’t think we can see the same rate of growth over the next 10 years that we have seen over the past 10 because that would get us into (larger) medium-duty trucks and perhaps even challenge Class 6 or Class 7. From my perspective, that would not make sense.”

But that doesn’t mean we won’t see further increases in capability. “With properly designed and executed systems, we have been able to continue to grow capability,” says Slevin. “There is certainly a point where I don’t think it would be prudent to go further. We have not hit that limit yet. Our customers’ appetite for capability has not stopped either.”

A Logical Starting Point

Payload and towing capability serve as the starting points for any truck design.

“We set a target for what we want the towing capability to be for a particular program,” says Slevin. “Many factors go into establishing the overall rating that must be worked on in parallel.” These include braking capability; structural capability; vehicle dynamics capability, which would be the steering and handling capability; powertrain capability and powertrain cooling capability. “All of these work together.”

Producing an efficient vehicle requires a balanced approach. “It does not make sense to have a frame that is twice as strong as it needs to be if my driveline cannot handle the weight of the trailer,” says Slevin.

A good example of this balanced approach is the Ford Super Duty line. “We launched the current architecture of the vehicle in 2011,” says Slevin. Since then, we upgraded the frame and suspension. We upgraded the brakes in ’13. And in our most recent launch for ’15, we upgraded the powertrain with a turbocharger and some powertrain sensors. Basically, we had to touch all of those things in order to continue to grow the capability.”

Likewise, Ram Trucks has utilized a systems approach to achieve its impressive 30,000-lb. towing ratings for heavy-duty pickups. “When you make one system stronger, you have to make the other ones stronger,” explains Dave Snyder, manager, Ram 2500 and 3500 Heavy Duty engineering. “It is not like one is that much more capable than anything else.”

For instance, Ram Heavy Duty pickups saw a dramatic increase in capability in 2013. “That was an engine, transmission, suspension, frame, cooling and cool air induction — those are all things we touched to get those numbers. It is a systems approach. We looked at every system from front to back to make sure it met those numbers,” says Rod Romain, senior manager, vehicle integration, Ram Trucks.

An SAE standard helps ensure owners towing expectations are met and validates the published OEM capabilities. “From a trailering standpoint, we rely on SAE J2807 as our guideline,” says Romain. “This sets performance standards for propulsion on grade, vehicle dynamics, braking, system cooling, etc.” The purpose of SAE J2807 was to provide a well-rounded, all-encompassing standard. “Any one of the categories within SAE J2807 could present a different limiting factor. Obviously, the lowest limiting factor becomes your overall end capability.”

A Towing Standard Emerges

The SAE standard covers almost every aspect of towing performance. “SAE J2807 gives a really good overview of all of the towing parameters that engineers have to consider,” says Tom Wilkinson, Chevrolet.

The standard states that as trailer weight ratings have increased, engine characteristics like horsepower and torque, thermal performance and driveline durability are no longer the only significant factors in determining trailering capability. Combination vehicle dynamics and tow-vehicle hitch/attachment structure have gained in significance.

Ram Trucks was among the first to adopt the SAE towing standard. “SAE J2807 is the guideline that is used to determine trailer tow ratings for Ram trucks,” says Bryan Wright – powertrain synthesis and analysis manager. “Vehicle dynamics, braking capability, hitch capability, vehicle mass, GVWR/RGAWR, powertrain cooling and propulsion system capability all come into play. Powertrain propulsion capability is designed to meet or exceed minimum speed on Davis Dam grade, 0- to 60-mph acceleration response and 12% grade launch capability. For these conditions, the torque/power curve, along with axle ratios, tire sizes, transmission gear ratio, peak engine speeds and driveline component torque limits, are key design criteria.”

Keep in mind there is more to a good tow vehicle than simply power ratings. “Raw power is probably the least important factor,” says Wilkinson. “The chassis needs to be able to safely handle the weight of the trailer and enable the driver to safely and comfortably control the truck and trailer. Cooling is also a critical variable.”

The mass of the tow vehicle is another consideration. “The upper limits on trailer ratings are, as much as anything, a factor of the GVWR of the vehicle, which of course determines the class of the vehicle,” says Wilkinson. A 30,000-lb. trailer rating is probably bumping up against the limit for a Class 3 truck (1-ton pickup). “A truck capable of handling a trailer heavier than that would almost certainly have a GVWR that would put it into Class 4. That starts getting into issues of taxes, drivers’ licenses, etc.”

The current generation trucks all pump out massive torque compared to their counterparts of 10 years ago. “I like to use the analogy of a power screwdriver,” says Wilkinson. “Once you have enough torque to drive the fasteners you work with, other things become more important. How well does the tool fit your hand? How well does it balance? Does it control torque well or does it snap off screws? Do your hand and arm hurt at the end of the day?”

Size It for the Application

With the increased capabilities, the possibility of downsizing to a smaller truck that is still capable of towing the necessary equipment is a real consideration.

“We have had a lot of discussion around the question of HD buyers moving down to a light-duty pickup, or light-duty drivers moving down to a midsize truck, such as the Colorado or Canyon,” says Wilkinson. “Ultimately, the customer needs to decide, so from our perspective, more choice is better. The Colorado can tow up to 7,000 lbs. when properly equipped. But I think the consensus is that if you are towing that much trailer on a regular basis, you may find a light-duty or even a heavy-duty (HD) pickup a better choice. It’s the same with a light-duty pickup. A Silverado and Sierra can tow up to 12,000 lbs. when properly equipped. But again, if you tow that much on a regular basis, a HD pickup with a diesel engine and diesel exhaust brake is probably going to feel more confident in the mountains.”

The decision comes down to what you’re trying to accomplish. “If you tow a trailer occasionally, a smaller truck can get the job done and will be more economical and more enjoyable for the 98% of the time it doesn’t have a trailer behind it. But for customers who tow a heavy trailer regularly, it is hard to beat a 3/4- or 1-ton HD pickup with a diesel. Many commercial customers find a gas-powered HD a good compromise. The initial cost is much lower than a diesel, yet the truck has real HD capability when you need to tow a heavier trailer.”

Fuel economy can also play into the equation. “There are no simple answers to the fuel economy question,” says Wilkinson. “Engine displacement is just one of many variables that determine real-world economy, so there are really no rules of thumb.”

Consider the pros and cons of smaller displacement engines. “At lighter vehicle loads, a smaller displacement diesel engine will produce better fuel economy than a larger displacement engine at the same load,” says Wright. “An incremental reduction in engine displacement in a loaded truck will typically cause the fuel economy to be similar, or in extreme cases, degrade below those of the larger engine.”

This can be due to several factors:

- In boosted diesel engines, a smaller displacement engine would require increased engine speed to deliver the greater power levels of a larger displacement design.

- Final drive ratio increases to deliver comparable grade launch capability as a larger displacement engine. This will cause engine operating speeds of the smaller displacement engine to be higher than the larger displacement engine at the same vehicle speed.

- Increased boost pressures result in higher fuel flow demand.

- There is decreased transmission efficiency associated with the higher engine speed requirements.

- An increase in torque converter clutch unlock conditions is required for acceleration, causing a loss in efficiency and higher engine speeds.

- Emissions impact: In general, smaller engines must work harder and produce more NOx, leading to more expensive aftertreatment up to and including more urea usage on SCR applications.

- Smaller displacement diesel engines may require the benefits of additional transmission gear ratio spread and lower gear ratios (e.g., eight-speed transmissions) to provide the capability to get loads moving while maintaining vehicle driveability and fuel economy.

How often will you tow? “If you are towing a heavy trailer on a regular basis, there is no question that a diesel HD will give the best fuel economy,” says Wilkinson. “If you only tow occasionally, a smaller pickup will be will be much more economical overall, even if it has worse fuel economy with a trailer behind it.”

But engine displacement is only part of the overall efficiency equation. “Would you be more efficient with a smaller displacement diesel engine in a heavy-duty pickup or chassis cab vs. a (larger) medium-duty truck? The answer is generally yes,” notes Slevin. “I am an engineer, so I am always going to think of that odd situation where something may not be true.”

The reasoning is more complicated than simply engine displacement. Consider that the GVWs in the Ford Super Duty line go up to 19,500 lbs. on the F-550. “Our medium-duty starts at 26,000 lbs. and goes to around 37,000 lbs.,” says Slevin. “As you can imagine, the frame has to be much stronger. It is massive, it just weighs more. The axles, wheels, tires and everything that goes into that medium-duty truck, except the cab, needs to be heavier duty. You get a weight penalty with that.”

But even more important than the weight are the increased parasitic losses in the axles, transmissions, etc. “Turning over great big ring gears in that rear axle takes a lot more energy,” says Slevin. “The heavy-duty pickup or chassis cab, when you look at the vehicle as a whole, would be much more efficient, particularly if you do any amount of driving unloaded. The unloaded fuel economy difference would be huge.” Slevin uses an example of a smaller car carrier that has a four- or five-car capacity. “I would want to use a heavy-duty pickup or chassis cab vs. a medium-duty truck because it is going to be more efficient, especially since a significant amount of the time would be unloaded.”

Ram has seen some of its customers take advantage of the newfound capabilities. “We have seen Class 6 owners move down to our Class 5 trucks,” says Romain. “The investment is significantly less. And depending upon their vocation, the capability is more than adequate. We have also seen in the past seven to eight years the new vocation of ‘hot shot driver.’ Customers who were formerly Class 7 or Class 8 independent freight haulers bought themselves a dually. Now they are hauling freight with a 3500 pickup.”

You really need to understand your duty cycle before making a decision to downsize. “The engine should be sized right for the job,” explains Romain. “There is a crossover point where it goes to less efficiency. It comes back to the right size engine with the right transmission ratios and the right axle for the job.”

“You still need to purchase your vehicle for the worst case load condition or capability,” says Troy Davis, head of Ram Chassis Cab engineering. “The capability has to match your criteria.” Durability is a consideration, so you need to consider the duty cycle. If you are going to haul 30,000-lb.-plus loads on a continual basis, you probably want to step up to a medium-duty product.

“Pick the right tool,” Slevin advises.