By Ray Master & Lawrence Dany

Improvements in our approach to safety over the past decades have led to a significant reduction in workplace incidents. In general, workers are safer now than at any time in history. In the past few years, however, a disturbing trend has appeared across several industries and countries — the number of non-fatal injuries has continued to fall while the number of fatal and catastrophic events has remained the same or increased. Employers thus remain legally exposed to the most serious types of incidents.

This situation is troublesome in an environment where regulators have become increasingly aggressive in investigating and imposing penalties for deemed safety failures, and raises the questions of why such incidents persist and what can be done to reduce the associated legal risk. One possible answer to both of these questions is for employers to reassess a basic assumption underlying many safety management programs.

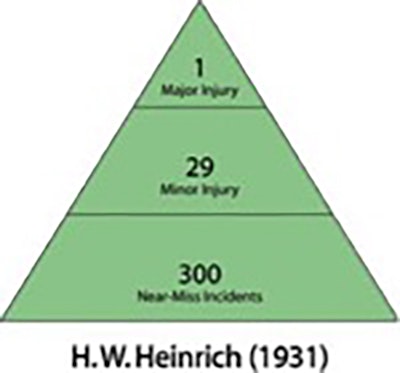

The basic assumption: the Safety Pyramid

One of the most ubiquitous safety models has been the Safety Pyramid, originally proposed more than 80 years ago. The pyramid model’s early success was due to the elegant display of simple statistical relationships between the types and severity of incidents and injuries — from near misses to fatalities. Although the model has been seriously critiqued over the years, it still persists as the primary model for explaining safety problems.

The model proposes that the probability of serious or fatal accidents (at the top of the pyramid) is correlated with less severe injuries or near misses (at the bottom). If true, then a remedy for serious accidents would be to reduce the number of less severe incidents.

Up until recently, safety leaders have indeed interpreted spikes in near misses or lost work days as an indicator that a more serious injury is more likely to occur, and that drops in near-misses and minor events indicated a major incident was less likely to occur, and the system was working as planned. Safety systems are then examined and modified, or validated and maintained as sufficient, based on such information feedback.

But, the foregoing assumptions are now being proven false. Fatalities and catastrophic events have remained constant or, in some places, have increased while minor injuries have continued to decline. This result is likely due to the fact that work today is increasingly complex, and failures which occur in these complex situations cannot be easily explained or understood by looking through the lens of simple tools developed for simple systems.

For this reason, there exists a systemic risk that companies may conflate consistently low, adverse-outcome numbers on low-level incidents with the adequacy of the overall safety system to control fatal or catastrophic events. Where the data indicates low-incident count, the conclusion may be that the system is working as planned (i.e., “safe”), and therefore not be subject to as intensive a review and audit as may be prudent under the circumstances.

This basic assumption underlying safety management may actually hinder risk assessment if risks are missed and not controlled because feedback indicates the system is safe. Usually, those missed risks and controls are associated with fatal and catastrophic events. Indeed, this condition may establish one root cause of process failure underlying a catastrophic event because when a catastrophic event occurs it is perceived as being “unexpected.”

Challenging the basic assumption to reduce legal exposure

In the event of a safety incident, and especially a fatal or catastrophic incident, a primary legal question will be the robustness of the company’s safety processes and procedures. In response to a civil suit or regulatory inquiry, the company will need to demonstrate that its safety management program met the applicable standard of care — that the employer’s measures were reasonable under the circumstances to identify and control known or foreseeable safety risks.

The applicable standard of care requires, among other things, a process for review and evaluation of program effectiveness, and for taking corresponding corrective action. When a safety program comes under scrutiny, one typical argument in defense of program effectiveness is a track record of good performance data on low-level incidents (wearing personal protection, near-misses, etc.) based on the logic of the Safety Pyramid.

But, current data suggests that conclusion may not be sound in complex environments that risk catastrophic incidents. When a program comes under scrutiny, offering evidence of consistently low, adverse-outcome numbers on low-level incidents as proof that the overall safety system adequately controlled the risk underlying a fatal or catastrophic event may no longer be valid.

Employers should therefore re-evaluate their safety management programs to determine if there is an inference or assumption — whether formal or informal — that low-level events are indicators of catastrophic or other high-level risk. Employers should ensure that their safety management programs are being reviewed and audited based on actual site and work conditions because those conditions change and are not dependent on a possibly dated assumption.

Diligently documenting specific processes used to identify and control the categories of catastrophic risk (e.g., fire), as well as the consistent review and evaluation of program effectiveness to control that risk, are initial steps to possibly mitigate legal exposure in the current environment.

Lawrence Dany is a partner at Sutherland Asbill & Brennan LLP in New York, NY. He represents clients in a wide variety of complex commercial, construction, financial services, real estate and white-collar litigation and arbitration across the country. As part of the Sutherland Construction Industry Practice Group, he represents construction managers, general contractors, industrial contractors, specialty contractors and their surety companies in disputes related to complex construction projects, including breach of contract, change orders, schedule delays, lost productivity, mechanics’ lien issues, payment and performance bonds and insurance. Larry’s practice also involves process safety litigation, occupational health and safety litigation, and industrial and construction workplace incident response. He is a member of Sutherland’s Crisis Management Team. When alleged violations arise, Larry guides internal investigations, prepares strategic responses to inquiries and defends entities in connection with investigations and enforcement actions brought by government agencies.

Ray Master is the Director of Loss Prevention/Safety Consulting Services. Ray brings 26 years of extensive experience in the field of construction safety. As a recognized leader in his field, Ray has served in a variety of construction safety roles across a wide range of industry markets to include general building, power, transportation, infrastructure, oil/gas, mining, emergency response and hazardous materials clean-up for both public and private construction stakeholders. His field project experience has brought him to over 12 U.S. states, four countries on three continents across the globe. His expertise focuses on and he is uniquely qualified to address both the technical systems aspects of safety and the cultural/organizational capacity for leadership and high performance in construction safety. His recent area of focus is on fatality and catastrophic event prevention. Ray holds a BS and MS in Safety Sciences from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. He has held adjunct faculty positions at both NYU’s Schack Institute of Real Estate and Columbia University’s School of Continuing Education’s MS program in Construction Administration His former employers have included JMJ Associates, industry leaders in organizational transformational, leadership and high-performance (Senior Consultant); Lend Lease, global construction and project management firm (Vice President, Region Director of Safety & Health – New York); CH2M Hill, global engineering, design and project delivery firm (Technical Consultant); Stone & Webster Engineering Corporation, global engineering, design and construction firm (Sr. Safety Engineer). He is nationally recognized as a Certified Safety Professional by the U.S. Board of Certified Safety Professionals. He also holds certification as an executive performance coach. Notable projects and roles include Lead Construction Safety Director – World Trade Center Disaster Recovery Project; and Safety Director/Site Safety Manager – 130 Liberty/Deutsche Bank Post-Fire Recovery/Abatement & Deconstruction Project.