Things Petrography Can and Cannot Do….

Cracks. Blisters. Spalling. Scaling. Delamination. Low Strength. These are sources of dissatisfaction for owners and aggravation for contractors involved in concrete construction. Because petrography is often used to investigate the causes of these problems, you should have a basic understanding of how petrography works and what its capabilities and limitations are.

What is petrography?

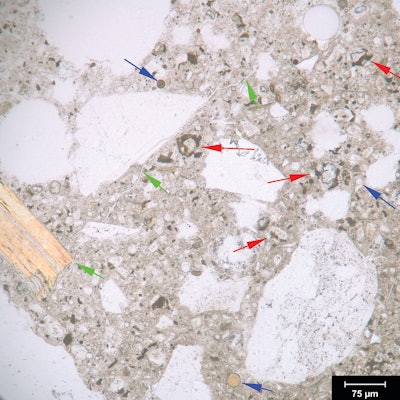

Figure 2. Petrographic microscope image. Plane-polarized transmitted light photomicrograph of a thin section showing detail of cement paste. The image was taken at 200x magnification. The red and blue arrows indicate relict and residual cement grains and fly ash particles, respectively. The green arrows highlight a microcrack.

Figure 2. Petrographic microscope image. Plane-polarized transmitted light photomicrograph of a thin section showing detail of cement paste. The image was taken at 200x magnification. The red and blue arrows indicate relict and residual cement grains and fly ash particles, respectively. The green arrows highlight a microcrack.

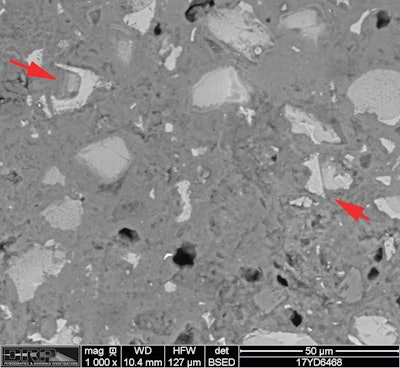

Petrographers do most of their work with microscopes that use reflected light (stereomicroscope), transmitted light (petrographic microscope) and electron beams (scanning electron microscope, SEM) to identify basic components in concrete, study cracks and microcracks, and identify secondary deposits that form when concrete deteriorates, such as gel from alkali-silica reaction. Figures 1-3 show examples of images produced from these microscopes. With the SEM, petrographers can even map the chemistry of concrete on a microscopic scale (Figure 4).

Petrographers learn a great deal not only about what is in the concrete, but how workmanship and environmental conditions affect performance. A huge advantage petrography has over any other test method is that it allows us to see concrete elements through their thickness, rather than relying only on an exposed surface for information (Figure 5). Petrography can determine if problems are surficial or run deep into the concrete, which is a key to developing repair methods that satisfy the owner’s requirements and preserve the contractor’s profitability. For example, a petrographic examination can demonstrate that a simple grinding treatment will suffice for a repair, rather than an expensive overlay or a needless removal and replacement.

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscope image. Backscatter electron micrograph of polished surface showing detail of cement paste. The image was taken at 1000x magnification. The red arrows show examples of relict and residual cement grains.

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscope image. Backscatter electron micrograph of polished surface showing detail of cement paste. The image was taken at 1000x magnification. The red arrows show examples of relict and residual cement grains.

What can concrete petrography do?

Evaluate proportioning. Petrographers typically describe the coarse and fine aggregate, identify cementitious materials such as portland cement, fly ash, slag cement and other supplemental materials, and describe voids associated with air entrainment, entrapped air, bleeding and consolidation. Point counting methods (e.g., ASTM C457) can quantify the proportions of aggregate, paste and air and determine if the parameters of air void systems are suitable for freeze-thaw durability.

Evaluate mixing and consolidation. The distribution of components in the concrete provide important information on mixing and consolidation. Poorly mixed concrete may show sand streaks, low w/cm mortar coatings on aggregates and clustering of air voids. Large voids, honeycombing and gaps around aggregate particles can indicate poor consolidation. Aggregate segregation and loss of air can indicate when and where over-vibration occurred.

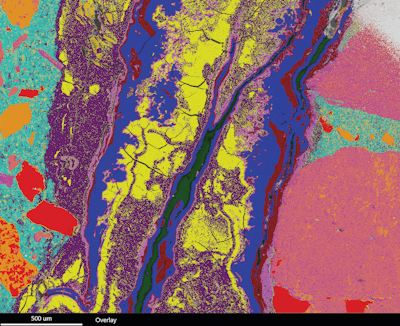

Evaluate causes of low strength. Low strengths can result from problems with batching and proportioning, such as excessive air or the presence of fly ash in what is supposed to be a straight cement mix. Retempering and excessive water additions are also common causes of low strength and can be recognized with petrography. Improper sample preparation is another cause of low strength test results and petrographic examinations can detect when this occurs.  Figure 4. Energy-dispersive x-ray spectrometer (EDS) map of concrete with a combination of sea water attack and alkali-silica reaction (ASR). The different colors represent different phases or compounds with distinct chemical compositions. The purple and yellow areas are ASR gel. The blue areas represent brucite (magnesium hydroxide) and the red/brown areas represent hydrotalcite (magnesium silicate hydroxide), which are produced from sea water attack.

Figure 4. Energy-dispersive x-ray spectrometer (EDS) map of concrete with a combination of sea water attack and alkali-silica reaction (ASR). The different colors represent different phases or compounds with distinct chemical compositions. The purple and yellow areas are ASR gel. The blue areas represent brucite (magnesium hydroxide) and the red/brown areas represent hydrotalcite (magnesium silicate hydroxide), which are produced from sea water attack.

Evaluate finishing and curing. Almost anyone can identify the type of finish (hard trowel or broom, for example) with a naked eye, but petrography can unveil much more about finishing operations. For example, petrographers are often able to determine if finishing was timed appropriately by looking at properties of the paste at and just below the finished surface. Inconsistencies in materials can also explain why some loads were more difficult to finish than others. Petrographers can evaluate curing by looking at the degree of hydration at the finished surface and measuring the depth of carbonation. Petrographers can also detect the presence of some curing compounds.

Evaluate cracking. Cracks come in all shapes and sizes. Petrographers can often attribute cracking to mechanisms such as early-age drying shrinkage, plastic shrinkage, thermal cracking and various durability mechanisms. Petrography can also determine the amount of microcracking, which may not be visible in a field survey but can be critical to performance and durability.

Identify durability mechanisms. Petrography is probably the only accepted method to determine many of the cause(s) of concrete deterioration that are related to durability. Petrographers can tell if concrete is deteriorating from freeze-thaw damage, alkali-aggregate reactions, chemical attack, corrosion, and more. Petrographers can help understand issues such as floor covering failures, which can result from moisture migration, durability mechanisms and installation issues. Identifying the extent of these mechanisms is often crucial to understanding why something is cracking, delaminating, or blistering five years after a project was completed (and paid for) and developing an appropriate repair.

What can’t concrete petrography do?

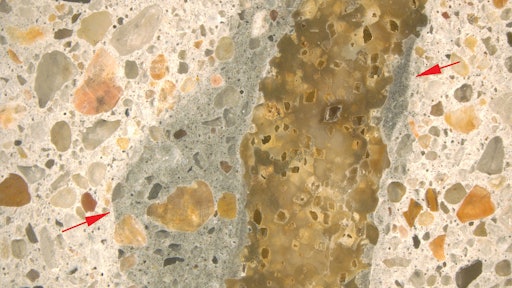

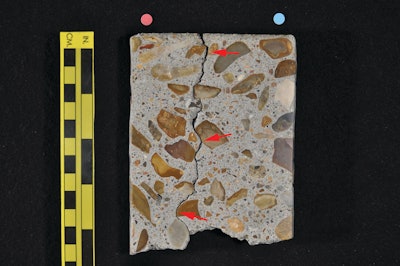

Figure 5. Photograph of polished surface of a concrete core taken through a slab on ground. The core represents the full thickness of the slab; the red arrows indicate a shrinkage crack that cuts through the full depth of the slab. The yellow bar is about 150 mm (6 in.) long.

Figure 5. Photograph of polished surface of a concrete core taken through a slab on ground. The core represents the full thickness of the slab; the red arrows indicate a shrinkage crack that cuts through the full depth of the slab. The yellow bar is about 150 mm (6 in.) long.

Most importantly, know that petrography alone won’t solve all of your problems. Most of the time, petrographers never see the actual jobsite and are relying on a small number of cores to evaluate jobs that involve hundreds of yards of concrete. Petrographers need personnel familiar with the jobsite, ideally a neutral accredited investigator such as a P.E., to provide a context for understanding how what is seen under the microscope relates to the bigger picture.

Author’s Note: This article updates and tries to build on a foundation (excuse the pun) provided by my friend and mentor, Lt. Colonel James A. Ray. He was old-school and one of the good guys, and wrote the original articles titled “Things Petrographic Examination Can and Cannot Do With Concrete, Parts I & II,” that were presented at the International Cement Microscopy Association conferences (www.cemmicro.org) in 1983 and 2000.