It’s Q4. You’re working feverishly to finish up your work before winter gets here (for most of you, that is). And you start seeing emails, letters, commercials, etc. about how you should take advantage of the latest and greatest tax laws to save tax dollars on all that money your company made in 2018. Is it a good idea? Maybe.

Let’s think this through. First of all, I’m going to assume you took my past advice to get a handle on your company’s 2018 tax position, so you could test out the new laws to see what you need to “shave” off your tax bill to get out of the top brackets. The same goes for your state tax position, which may mirror the federal laws and then again may not. Who knows — your company may even have loss carryovers from prior years that will eat up 2018 profits.

If your company winds up with a lot of high-bracket taxable income, then thinking about buying a piece of equipment for tax reasons may make sense. But if you find yourself in the lower brackets, the tax savings you get may not offset the financial obligation you are taking on. In the end, I would not make a “tax” purchase unless I knew it was offsetting top bracket tax dollars.

Factor in Equipment Utilization

If your business is in the top tax brackets then you pass Test #1. Test #2 will deal with the time utilization you get from a machine you purchase.

I would say 70% to 75% of your work days should find the equipment you’re contemplating purchasing on a jobsite and being billed to the job. I know that sounds like a lot of days. However, I spend a lot of days in the equipment rental industry and we shoot for 65% to 75% billable time utilization. If we don’t hit that goal, we are looking at why and whether we should keep the unit because it may not pay for itself.

Like you, I need to make sure what I bought for my rental fleet is making me a buck. I need my equipment to be out on the jobsite and I need both a certain time and dollar utilization to cover the cost of the equipment as well as the cost of renting it out. If I can’t rent it for some minimum time period that ensures I obtain annual rental dollars that cover the nut, I’m not going to keep that equipment. You’re in the same boat when you consider how much you are billing for the equipment against the cost to own and operate it.

Whether you pass Test #2 has to be calculated by you. To pass, you need to come up with at least a 35%+ cost recovery (30% to 40% is expected) for the first full year of ownership. If not, I would think twice before buying more equipment for tax purposes. Even if you passed Test #1, you might give back those tax savings, and then some, because of inadequate time and dollar utilization.

Cost Recovery Calculations

To calculate your billings against costs, let’s go through an example that kind of parallels my rental metrics. We will use $100,000 for the purchase price; you can simply apply the percentages to the cost of what you are contemplating buying.

A time utilization of 75% should provide billings that are at least 35% to 40% of the cost of the equipment. The percentages I’m using relate to larger pieces of equipment. Lower cost items will normally have higher annual recovery rates (50% or higher) because they wear out faster.

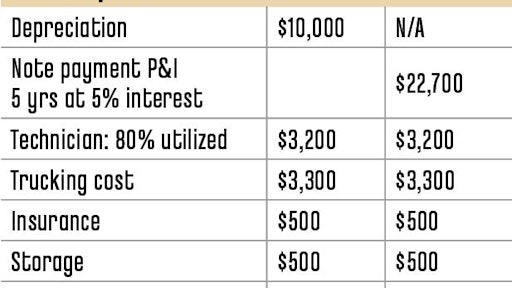

Now let’s review the example at left. For easy figuring, I used a $100,000 expenditure financed at 5% over 60 months. Book depreciation is 10% per year. (Why is a matter for another column.)

The technician and trucking costs include the service tech, driver and truck. I assume your techs are utilized 80% of the time working on equipment, or being charged to a job doing some other type of work. The same assumption goes for trucking costs. I move units around about three times per month. If your number of moves are higher, then your trucking costs will be higher.

Trucking costs for both driver and truck are estimated at $5.40 per mile or $115.00 an hour. Parts and fuel are the other major expenses to consider.

In the example, the $100,000 purchase is charged to jobs at $35,000 per year. I offset this against a billing of $19,350 in direct expenses related to owning that equipment, resulting in 45% revenue over cost. This is a nice recovery margin — or is it?

The cash flow numbers tell a different story. It’s just about a break-even when I use the note payment instead of depreciation.

So, if you don’t bill at least $35,000 a year for a piece of equipment you purchased for $100,000 — and have highly utilized techs and drivers plus a parts source where you get a discount — I highly doubt you will achieve a positive cash flow result buying equipment to save money on taxes.

This gets even more complicated when you consider the full 60-month financing cycle and beyond. Of course, if you keep the equipment properly maintained so that you can use it post debt service, then your overall return will increase.

The point here is there is not a lot of wiggle room when it comes to a rent/buy decision. If you pass Tests #1 and #2, then by all means make the purchase if it will be cheaper than renting. But if it’s tight, you may be better off renting to avoid all the costs of ownership; those costs move to the rental company, giving you more control of both your short-term and long-term operating results.

If there are any questions, you can reach me via the contact information provided below.