If you have the right the tool for the job, it goes a long way to getting the job you're doing, done correctly. What do you do if there are multiple "right" tools? How do you decide which one to use? When it comes to the type of screed on your paver, as an operator, you might not get a choice. You have to work with what you've got, but that doesn't mean there isn't value in understanding how the different types of screeds work in various conditions. While they might all be capable of completing the job, the way each operates can mean subtle differences in the end result. Knowing what makes them different could make you reconsider previously held assumptions about screed technology.

The Different Types of Screeds: Front and Rear Mounted Extendable Screeds

A screed is the very backbone of the paving process. It largely determines the quality of mat smoothness, as well as initial compaction. The three most common types of asphalt screeds are widely implemented in models across the United States, however, there's a fourth variety of screed that is very popular in the global market that only sees limited, or specialized usage in North America. We'll discuss that one down below, but let's first cover the two that most contractors and operators are most familiar with.

Front and rear mounted extension screeds, by far, dominate the domestic U.S. market. On the front-mount screeds, the extensions are out ahead of the main screed, whereas on the rear-mounts it's the opposite. The main screed sits ahead of the extensions.

"These two can do the exact same scope of work," said Tom Travers, Director of Technical Sales at Astec Industries. With forty-five years in the paver market, and more than half of those years working on the back of a paver, Travers speaks from a place of solid experience. "The value of the front-mount is that, when you extend and retract your extensions to accommodate the footprint you're trying to cover, you do it with less force on the screed. This is because the head of material stays out in front of the product."

Traver's isn't the only one evangelizing the ways of the front-mount screeds, Bill Laing, Director of Engineering, Blaw-Knox Corporation, also speaks to the benefits of their design. "With front mounted extensions, you can keep the head-of-material confined and in front of the screed. By and large, they do that easier than a rear extendable screed."

For jobs where you might be frequently making adjustments to the width of the paving foot-print, these offer the benefit of reduced force, but that, also can translate into less wear, less frequent maintenance, and a slight reduction in fuel consumption. Additionally, when retracting the width, front mounted screeds can bring the material back into the center without fear of "pinching" it.

However, read-mounted screeds aren't without their benefits. "They can both do anything from commercial to heavy highway paving, and do it well," said Laing. "The difference is a rear-mount screed extension plate has the same depth as the main plate. So, there is way more uniformity in the plates that are installed on those machines." Say a main screed is twenty inches deep, then extension is also 20 inches inches deep. This results in a very consistent mat quality.

Front mounted screeds have unequal extension depth vs the main screed depth. To overcome this difference front mounted screeds require an additional adjustment, the individual angle of attack for the extension. For example, if the main screed is twenty-four inches deep, the extension could be set to ten inches. In order to have uniformity of texture, you nose the extension up higher, forcing more material under it in order to match the texture a deeper plate naturally provides. Despite this small extra step, Laing doesn't think impact the decision between the two types of screeds.

"Both products will perform just as well in the same environment," Laing said. So, the questions is: what is the main driver behind which type of paver is selected, between front and rear mounts?

"A lot of what determines whether a company runs a front-mounted or a rear-mounted screed, is what they know," said Travers." People are reluctant towards what they don't know, and asphalt workers even more so, are creatures of habit. It's a bit of a challenge to get a front-mounted operator to go to a rear-mount or the opposite, and, at the end of the day it has nothing to do what's best for the job."

This can be even more true when it comes to the third most common type of screed here in the United States.

Set It And Forget It: The Wedge-Lock Screed

The beauty of a wedge-lock, or a fixed-width, screed, if you're on a job that can utilize it, is volume it can lay down and the integrity of the mat quality. You build up the width of the screed for the day's scope of work, usually in two-foot bolt-on sections, and then you aren't concerned with the sorts of variables that extendable screeds are. This can be a great solutions for airports and long stretches of roadway, however, a lot of America's highways aren't necessarily built to suit that type of use.

"We're talking thirty-to-forty-year-old technology here, but it has its place," Travers insisted. "If you can maintain width for the whole day, then that's probably the product that works best. It's kind of a bullet proof product, and it requires a lot of finesse from a crew. When you go from a wedge lock to a power extendable screed, it takes a little bit more concentration from the crew."

While wedge-lock screeds can produce a highly consistent mat quality, and reduce segregation, it comes at a price. It's very time consuming. The end of the screed might be twelve or sixteen feet from the hopper, and, in order to achieve proper ride quality, it is usually required that auger segments be built out from the tractor no less than twelve inches from the end.

"It's at a great cost to the contractor," admitted Travers. "It's time, labor, and you have to have the iron there to do it. And although it should be done, some don't do it."

To get it done correctly, it takes a trained mechanic, and since usually the components are heavy, it can often require a support truck and/or a crane to build it up. When a contractor opts not to do it, and cut corners in the application, it is a risk they are taking. According to the experts, if the contractor thoroughly believes in best practices and best material placement, they should uphold the auger requirement, maintaining proper and consistent material flow in front of the screed.

Paving Across The Pond

In Europe and most other countries, they utilize a type of screed that only sees extremely limited, specific uses here in the United States. This is the case despite some clear benefits that they offer, and it brings back to mind the words of Mr. Travers earlier, that people pave what they know. However, when it comes to tamper-bar style screeds, it's goes beyond just habit. The whole methodology of European paving is different from how asphalt is laid in North America.

There's, there's a big difference in screeds in North America versus the rest of the world," said Kevin Comer, North American Vogele Product Director at Wirtgen Group. "European style paving is deep, wide, and slow. Here in the U.S. we pave, thin and narrow and fast So, tamper screeds don't get a lot work in our environment, because it is a different type of paving that requires slower paving speed."

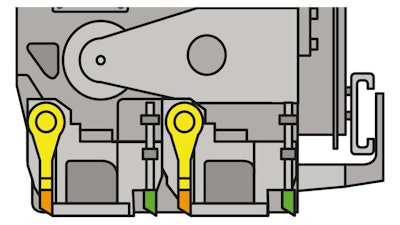

Diagram of a tamper bar (yellow) screed with a single pressure bar (green) at the rear.provided by Vogele, Wirtgen Group

Diagram of a tamper bar (yellow) screed with a single pressure bar (green) at the rear.provided by Vogele, Wirtgen Group

The Euro-paving style is driven by pre-compaction technology. The tamper bar kneads the material before it passes under the screed. At it's most basic, the tamper is a bar ahead of the screed that goes up and down in rapid cycles, like a piston. However, the technology is combined with vibration (on the screed), also, in addition to the tamper bar, two pressure bars (after the screed) can be added to even further improve levels of compaction.

The U.S. market is focuses on vibration, and picks up compaction through rolling. European paving picks up a larger percentage of their compaction as they lay the material.

As an example, if there were twelve inches of asphalt going down, in Europe, they would spend more time getting the base as flat as possible, and then lay a single layer ten inches deep, using a tamper bar screed, and then finish with a wear layer of two inches. Whereas, here at home, we would build up the road in three inch lifts, gradually smoothing out the surface, layer-by-layer.

"The tamper bar allows you to pave deeper lifts with improved compaction, therefore allowing pavers to pave larger lifts and excellent smoothness.," said Comer. "It's just a different way of building the roads, and there's a place for it in the American market, it's just not the most common."

It mostly sees use on specialized raceways, bridges, and other structures where extremely heavy compaction equipment is not a suitable or desirable option. However, it doesn't mean it couldn't see wider adoption as labor shortages and the cost of that labor increase. These types of screeds can reduce the overall compaction train, reducing the number of trained roller operators on a given site.