According to a newly released report by TRIP, “Keeping Maryland Mobile: Providing a Modern, Sustainable Transportation System in the Old Line State,” traffic levels in the Baltimore and greater D.C. areas returned to just under 5 percent of what they were prior to the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns, which saw a decrease of 47 percent.

One of the biggest revelations from the data collected by the report showed that the commuting situation, and the subsequent traffic congestion is costing drivers in the state a total of $5.8 billion annually, which amounts to approximately $2,500 a year per driver. That's no small amount for anyone. Provided by TRIP

Provided by TRIP

These losses take the form of directly wasted fuel, emissions, delays, missed hours, and, also, missed opportunities. And it's that last point that may be impacting the economy is ways not previously considered.

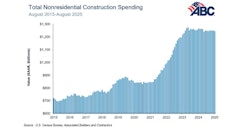

While the state of Maryland's level of highway investments will increase as a result of the five-year federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), signed into law in November 2021, which will provide $4.6 billion in road, highway and bridge funding in Maryland from 2022 to 2026, including a 36 percent increase in federal funding in 2022. What is even more interesting is related to the job and labor market impacts TRIP discussed in a press release dated May 2, 2023:

"Approximately 1.8 million jobs accessible within a one-hour drive to a resident of the Baltimore metro area, only 30 percent are accessible within 30 minutes. Of the approximately 2.4 million jobs accessible within a one-hour drive to a resident of the Washington, DC metro area, only 24 percent are accessible within a 30-minute drive. The Center for Transportation Studies report also found that the number of jobs accessible within 40 minutes during peak commuting times in the Baltimore and Washington, DC metro areas was reduced by 43 and 51 percent, respectively, as a result of traffic congestion."

It goes on to reveal that in 2020, before the pandemic changes traffic conditions, and, as previously established, traffic has now nearly rebounded to, less than 10 and 12 percent of the available jobs were accessible to those using public transportation in Baltimore and D.C. respectively, in under an hour long trip. For those using micromobility solutions, the numbers were even worse, coming in at 4.8 and 7.4 percent respectively.

Some of these figures and what is considered accessible or reasonable commuter times is dependent on personal perspective, financial situation, living situations, and, most importantly, access to personal transport.

However, if taken as an example for other similarly congested urban areas across the country, there are potentially millions of jobs remaining unfilled not because there aren't able and willing workers, but because workers cannot reasonably commute to the available positions within the city.

"Traffic congestion significantly reduces access to jobs and employees," said the TRIP report. "The report found that the number of jobs accessible within 40 minutes during peak commuting times in the Baltimore and Washington, DC metro areas was reduced by 46 and 52 percent, respectively, as a result of traffic congestion."

Of course, these figures go hand-in-hand with another current crisis, not just in D.C., but all across the United States. Affordable housing in areas of the city which would be more apt to take advantage of micromobility options and public transit is extremely hard to come by, bordering on nonexistent. According to a report by the Washington Post, in the wake of a scathing 72 page report from the District of Columbia Housing Authority Assessment, the editorial piece sums up, fairly well, the heart of the problems:

The root of the crisis lies a market in disequilibrium. According to the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, the region needs 320,000 additional units of housing by 2030 to accommodate burgeoning demand. Current production, said the group’s executive director, Chuck Bean, is about 8,000 to 10,000 units per year shy of that goal. The result is too many people chasing after too few homes. Literally chasing, too: As prices for inner-ring condos and homes go through the roof, workers with low and moderate incomes are forced to seek housing farther and farther away from bustling regional nodes, a phenomenon known as “driving till you qualify.” A line cook shouldn’t have to commute three hours a day so well-heeled diners can enjoy the appropriate amount of char on their gourmet burgers.

These issues intersect with another recent story on ForConstructionPros, where local real estate groups clashed with proponents of bike lanes and other micromobility solutions in downtown D.C., and while it doesn't offer a concrete causation, there is a relative correlate that can be drawn from both the TRIP report and the bike lane controversy. Read that story here for more context on the issues.