The Cornell Program in Infrastructure Policy (CPIP) explores policy aspects of infrastructure deployment: design, construction, operation, maintenance, procurement, funding, financing, and recycling of assets to ensure efficiency, cost‐effectiveness, equity, and inclusion.

CPIP encourages the incorporation of the latest technologies – sensors, robotics, artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, low‐carbon materials, and data analytics – into new infrastructure projects.

The program’s scope includes heavy civil infrastructure such as roads, bridges, tunnels, airports, seaports, drinking water systems, wastewater treatment facilities and energy systems.

Professor Rick Geddes is the founder and academic director of CPIP, which started in 2012 and focuses on peer-reviewed research, teaching, and public engagement and outreach. Its 40-member industry advisory board represents, “some of the most distinguished people in the infrastructure world,” he said.

Among CPIP teachings is, ‘climate engineering,’ a term Geddes said Cornell University developed to emphasize the new technologies that have been developed in the infrastructure world.

Professor Rick Geddes, Academic Director and Founder of the Cornell Program in Infrastructure Policy stands before the Edinburgh Futures Institute at Edinburgh University in Scotland, where he was collaborating with the Centre on Future Infrastructure on research regarding hydrogen hubs for vehicles in June, 2024.Rick Geddes

Professor Rick Geddes, Academic Director and Founder of the Cornell Program in Infrastructure Policy stands before the Edinburgh Futures Institute at Edinburgh University in Scotland, where he was collaborating with the Centre on Future Infrastructure on research regarding hydrogen hubs for vehicles in June, 2024.Rick Geddes

“I call it a quiet technological revolution, because we hear a lot about driverless cars and electric cars. But there's a whole set of other technologies that includes sensors embedded in concrete and elastic asphalt,” he says.

Geddes notes the work of Cornell University Materials Science and Engineering Professor Emmanuel P. Giannelis who was instrumental in developing new materials for roads and highways to decrease the rutting and cracking that typically takes place especially during freeze-thaw cycles.

“We developed a new family of surfacing materials by incorporating clay nanoparticles into asphalt,” Giannelis says. “These particles are chemically similar to those found in soils except for their size, which is much finer. Specifically, they have at least one of their dimensions in the nanometer range and they can mix with the other ingredients at the nanoscale.”

As a result, adding a small amount of nanoclays leads to significant improvements in mechanical and thermo-cycling performance, Giannelis explained.

“In addition, the nanoclays allow replacement of more expensive copolymers and other polymer additives with the lower cost crumb rubber. The technology offers significantly improved performance compared to traditional surfacing materials leading to roads with longer-lasting surfaces, even under extreme weather conditions.”

The technology is currently being scaled up and tested in real applications and is a good example of a new type of partnership where academia works with private, government, and corporate partners to develop critical next-generation technologies, Giannelis explained.

“I believe there's a lot of other innovations in asphalt and these materials that needs to be studied more and tested,” he says. “They key is adoption at scale, where you try to figure out new materials to get more with less or more with the same, so you don't have to resurface as often. It's more environmentally friendly. That’s the climate engineering we're trying to get across.”

Making The Case For Tomorrow

Another policy topic CPIP investigates is ‘future-proofing.’

“It’s a bit of a misnomer, because we can't protect ourselves from the future,” Geddes noted. “But the idea of future-proofing is if you have a procurement contract with a private partner to do operation and maintenance, that contract includes clauses in it such that the private partner has a duty to utilize the latest technologies in their operation and maintenance of the infrastructure.”

Geddes said that as a professor of economics, one factor on his radar is the lack of proper pricing of the use of the transportation infrastructure, creating challenges in building and rebuilding roads.

The Cornell Program in Infrastructure Policy exists to “educate the next generation of infrastructure leaders”. Here a class celebrates the completion of an intensive seven day bootcamp in designing spreadsheet models for infrastructure finance in January, 2024.Rick Geddes

The Cornell Program in Infrastructure Policy exists to “educate the next generation of infrastructure leaders”. Here a class celebrates the completion of an intensive seven day bootcamp in designing spreadsheet models for infrastructure finance in January, 2024.Rick Geddes

“It’s very difficult to price all roads immediately, but we have seen a lot of incremental steps like congestion pricing in New York City," he said. The program, which had been postponed, is rolling out in a modified version beginning Jan. 5.

“One of the things that bothers me is that the economics and technology now is available to do that properly, but we seem to fail on the political side,” Geddes says. “How political a lot of the policies become in transportation is disconcerting.”

Additionally, Geddes said he understands the encouragement of using electricity rather than fossil fuels, but EV drivers aren't paying anything for the use of the roads under the current way they are funded at the state and federal level. He points out many people – particularly younger people – have equity concerns associated with the gas tax.

“It was greatly increased in 1956 at the federal level by President Eisenhower to pay for the construction of the interstate highway system,” said Geddes. “In those days, any four-door family car got about the same mileage per gallon. If you bought a gallon of gas, you would use the roads about the same amount.

“Today, that’s no longer true. A wealthier person who has a Tesla pays zero in the gas tax. But a poorer family with a less energy-efficient old pickup truck pays a heck of a lot.”

Geddes noted federal taxes on fossil fuels per gallon stand at 18.4 cents for gas and 24.4 cents for diesel.

“The uptake of electric vehicles means there's less use of fossil fuel and less tax revenue is going to be more correlated with this inequity problem,” explained Geddes. “The Department of Transportation has to fund itself somehow and you're pushing that cost onto the gasoline drivers who tend to be lower income. Gas tax is regressive in the sense that it hits poor families more than rich families.

“They are not indexed to inflation, so inflation, over time, erodes the purchasing power of those fossil fuel taxes,” he said. “That’s also true at the state level.”

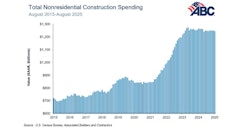

Geddes said that the cost of construction materials has gone up faster than the consumer price index against the backdrop of declining revenue. He added that he understood the reason for the shift away from the use of fossil fuels for environmental and other reasons, but calls it a paradox, “because you're trying to fund your transportation network based on the consumption of fossil fuels at the same time you're trying to discourage the use of fossil fuels.”

The Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards that were increased at the end of the George W. Bush administration and the beginning of the Obama administration have been tightened over time, Geddes said.

“The idea is to encourage more efficient vehicles and discourage use of fossil fuels and the car companies complied. They figured out more efficient engines,” he added. “But the effect of that on the tax revenue for transportation at the state and federal level declines as a result.”

Geddes backs the idea of switching to a road usage charge, such as used in Oregon.

“You pay a flat fee per mile of road use. You separate the use of the road from whatever fuel you use,” he said. “There is a solution to this, but it’s the political will that’s lacking.”

Transportation Reformation

Geddes talked of the reform of the National Environmental Policy Act, dating to January 1, 1970, requiring federal agencies to assess the environmental effects of their proposed actions prior to making decisions.

“It was thought to be a modest bill, but it's become a giant barrier to the efficient delivery of infrastructure in the United States,” he argued. “The effect of delaying projects is to make them more costly. It slows them down enormously. I think it slows the adoption of new technologies.”

Another consideration is examining the way the U.S. has delivered infrastructure for about a century – particularly with taxes on municipal bonds, which tends to discourage partnerships between the public and private sectors, Geddes said.

“A lot of times, private partners are the ones who have they do these projects globally,” he said. “They understand the technologies. They're willing to take risk. I’ve urged policymakers to undertake reforms of the way we deliver and procure infrastructure in the United States in order to encourage more public private partnerships.”

Geddes notes the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) increased the cap on tax-exempt highway or surface freight transfer facility bonds to $30 billion and that it’s his understanding the U.S. will hit that cap soon.

“I would urge no cap as long as it's a qualified project,” he added. “The Treasury claims it would lose revenue, but we can debate how much that would be.”

Geddes added that the U.S. infrastructure is owned and controlled in a, “very balkanized fashion. There's a lot of very small owners of infrastructure. They’re used to doing procurement in a certain way and are a bit concerned about innovative techniques like public private partnerships that are regularly used in many other countries.

“My hope would be that the public sector could be trained. We call it public sector capacity – capacity is like the comfort level with innovative contracting, the knowledge, and the skills, so they protect the contract with the private sector more but also protect the public interest in the process of doing that.”

Public sector asset owners are slow to adopt new technologies because they're risk averse. Through CPIP, Geddes advocates innovative procurement contracts where the private sector assumes some of that risk through future proofing and insurance that tries to speed up adoption of those technologies by the public sector owners.

“The primary thing is to protect the public interest, but at the same time, we can't be stuck forever in a certain way of doing things,” Geddes said. “This quiet technological revolution in infrastructure offers us this chance to really leap forward.”

Resiliency Will Only Become More Important

The issue of road reconstruction as a result of climate change is a global concern.

“We are seeing, primarily due to recent events, that future infrastructure and adaptation, resilience, and risk for climate change is rapidly rising up in the discussions of governments, municipal authorities, and industry,” noted Professor Sean Smith, Chair of Future Construction, School of Engineering at the University of Edinburgh.

AdobeStock_390821353

AdobeStock_390821353

Transport infrastructure – along with buildings and housing – has taken some of the biggest hits from climate change, he added.

“Recent events both in Europe with Storm Boris and Hurricane Helene in the U.S. showed the catastrophic damage to highways, country and mountain roads – many of the key arteries for communities, business and inter-city movement of people and goods which have been so badly damaged,” he said.

“Many transport routes such as roads or rail have become the new rivers of climate change as they are the primary route map for the channelling of heavy intense storm rains prior to reaching rivers and deltas."

Fifty years ago, no designer or engineer foresaw the extent of intense rainfall many countries now face.

“The ferocity of slow-moving storms and intense rainfall experienced inland, well away from the coast, has made us all consider how we must redesign and adapt existing infrastructure or in-build higher resilience, well beyond anything we had planned before,” Smith added.

All local and national governments need to make greater headway in ensuring infrastructure resilience and adaptation is integral to annual spending plans, noted Smith.

“Learn from some of these key events and undertake infrastructure risk assessments and modeling to then focus funds to maximize resilience on key communities and industry areas,” he said.

Smith noted there is not necessarily any region that is not affected by climate concerns – case in point, Asheville, North Carolina. Earlier this year, Dubai experienced 18 months of rain in two days.

“Previous modeling needs to shift from the ‘what did we plan and know from before’ to ‘what we need to do to plan for the unknown’,” Smith explained.

Smith believes asphalt is still the best choice for road construction and replacement, “with a greater focus on enhanced reinforcement of roads – boundaries – and embankments and with the opportunity to potentially build in parallel pipework to draw the water away, most likely and easier to be surface mounted awaiting use once such storms arrive.”

Smith noted a country’s Gross Domestic Product should also be measured on its ability to reduce risk and inbuild infrastructure resilience.

“We don’t have much time,” he said. “The sooner we start, the better.”