A kit that retrofits static and vibratory steel rollers and challenges the long-standing method of relying on vibration to compact asphalt pavement is under development and is being tested in Canada.

Developed by Abd el Halim, a professor at the Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering and director of Infrastructure Protection and International Security Master Program at Carleton University in Ottawa, the new approach relies on a continuous piece of specially made rubber – essentially a belt or track – to provide more even and continuous contact with the pavement during the compaction phase.

Initially named AMIR (for Asphalt Multi-Integrated Roller) after Halim’s son, the roller kits have been tested and are produced under the name Trak by Tomlinson Group, a road and bridge contractor in Ottawa.

Russ Perry, vice president of heavy civil for Tomlinson, says the contractor was one of three to test the concept several years ago. “Once we saw how well it worked we were convinced,” he says.

Halim says the Trak design results in more uniform density throughout the pavement and extends pavement life by eliminating cracking, creating an impermeable surface that prevents water from entering the pavement.

A New Compaction Approach

Halim says that he became interested in a new approach to compaction in 1982 after witnessing small cracks appearing in the asphalt of a small paving job almost immediately following compaction. He says that each time the rollers go over the asphalt, they cause some degree of cracking because of the vibrations and uneven pressure being applied.

“Because of the compaction process you start damaging the asphalt the minute you make your road. And once cracks appear, you can’t fix them. You just try to minimize their damage,” he says.

After giving some thought to the problem Halim decided people were trying to improve every aspect of the paving job except no one was considering a new approach to the compaction process.

“I told people over the years they weren’t going to find a solution to the asphalt problem because they were looking in the wrong place,” he says. They weren’t looking at the roller, which has remained basically unchanged for years.”

So he built a prototype that relied on a rubber belt or track that wraps around the rollers like a piece of carpet. The approach was tested in Australia in 2000 and gained some interest but not enough to pursue development – until 2009 when Halim was asked at a conference what happened to his roller.

“I said my roller was collecting dust and I was told ‘Shame on you!’ I think a combination of changes in the industry, the demands of end users and interest from the Ontario Ministry of Transportation in extending road life resulted in more interest in the idea,” he says.

So he began pursing development of the roller again and decided early on that he didn’t want to create an entirely new roller that contractors would have to buy. Instead, he and Tomlinson spent four years developing a retrofit kit to replace the drums on existing rollers.

“That way contractors don’t have to buy new rollers to use this design,” he says. “They can just use the rollers they already have.”

How Trak works

Halim says most rollers today use two drums in the front and two drums in the rear. One Trak kit replaces one drum, so retrofitting one such roller would require four kits. He estimates that it takes up to four days to retrofit a roller with four Trak kits. Perry says that once a roller has been retrofitted with a Trak kit it can be swapped on and off in less than a day.

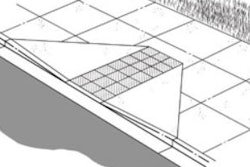

He says the steel drums are removed from the roller but the skeleton, frame and engine are all retained. Each drum is replaced by two large cylinders and three small cylinders. With Trak the five cylinders are wrapped with a specially designed flat “belt” or “track” composed of a number of layers of rubber. (Perry says the design is similar to a bulldozer if the steel tracks were replaced by rubber tracks.) Halim compares the rubber track to a piece of carpet because while it wraps around the cylinders, a large portion of it – almost half – is in continual contact with the asphalt.

“That’s really the most important part of the roller,” Halim says. “The roller is really about the rubber itself.”

To explain why the Trak doesn’t crack the pavement, Halim uses an analogy involving eggs. “Take two raw eggs. Stand the first egg vertical on a hard surface and using a spoon gently tap on the tip of the egg until it cracks. You’ll see it won’t take long for that to happen.

“Take the second egg and stand it vertically like the first on the same hard surface, but place your fingertip on the top and tap your fingertip and you’ll see it doesn’t crack.”

That’s because the fingertip, like the flat rubber track, disperses the impact of the tapping just like the rubber evenly disperses the pressure of the five Trak cylinders across a greater area of the pavement.

Density and Impermeability

Halim says that by using the rubber “carpet” the Trak provides uniform compaction over very large area -- as much as 75 times more contact with the asphalt -- as opposed to the narrow strip where a steel wheel roller contacts the asphalt.

Perry says the Trak is able to provide compaction because of the increased time the weight of the roller is on the pavement. “It’s just a factor of time,” Perry says. “It’s a little like a sandwich press that compresses the whole sandwich at the same time. You just apply the sheer weight over an extended area and for a greater period of time – as opposed to a nanosecond with a steel wheel roller.”

Halim says this broader coverage creates uniform pressure on the asphalt – the cylinders aren’t dipping into the asphalt like a roller does -- resulting in a greater reduction in the number of passes required and a more solid, crack-free asphalt surface. He says using the Trak roller reduces the number of passes required from more than 20 (using breakdown, vibratory and finishing rollers) to between six and eight.

Perry says users of Trak rely on a formula to determine the required pounds per square inch needed for proper compaction. Once that determination is made weight is added to the Trak and rolling can begin.

Halim says that because Trak provides uniform pressure across a broader area, it can compact thicker lifts of asphalt than traditional rolling methods. He says that where a traditional steel wheel roller can’t compact more than 50 mm without vibration, the Trak can compact as much as 150 mm.

“That means using the Trak you can place one lift instead of two, reducing the time on the job,” Halim says.

Perry says Trak has been especially effective for compacting asphalt on bridge decks where vibration can’t be used.

“Because you’re not able to use vibration on a bridge deck you’re not getting high levels of compaction anyway using only a steel roller,” Perry says. “This machine gets compaction levels as if you were using a vibratory roller.

“But density is not as important as permeability. If the pavement isn’t permeable, water can’t get in so the pavement will last longer.”

![Lee Boy Facility 2025 17 Use[16]](https://img.forconstructionpros.com/mindful/acbm/workspaces/default/uploads/2025/09/leeboy-facility-2025-17-use16.AbONDzEzbV.jpg?ar=16%3A9&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=135&q=70&w=240)