According to the National Asphalt Pavement Association (NAPA), the earliest HMA production units consisted of shallow iron trays heated over open coal fires. The operator dried the aggregate on the tray, poured hot asphalt on top, and stirred the mixture by hand. The quality of the mix usually depended on the skill and experience of the operator.

The Cummer Company opened the first central asphalt pavement production facilities in the U.S. in 1870. By the end of the 19th century, builders on both sides of the Atlantic were producing mixers and dryers in a variety of forms.

The first asphalt facilities

The first asphalt facility to contain virtually all the basic components we have today was built in 1901 by Warren Brothers in East Cambridge, Mass. (It lacked only a cold feed and pollution control equipment.) The first drum mixers and drum dryer-mixers, which came into use around 1910, were Portland cement concrete mixers that were adapted for use with HMA. Mechanization took another step forward in the 1920s with the improvement of cold feed systems for portable and semi-portable systems. Vibrating screens and pressure injection systems were added in the 1930s.

The asphalt plants of the early '50s might have included a dryer, a tower with a screed, and a mixer. They were dirty, dusty operations, says NAPA. But by the mid-'60s, with air pollution a serious concern across the country, many had added wet scrubbers and a few had baghouses.

The other major change in the mid to late '60s was the addition of surge bins and storage bins. Prior to that, everything was loaded right from the plant into the truck.

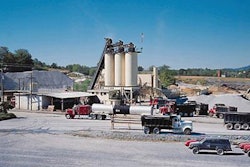

Today's asphalt production facilities have come a long way from the dirty, dusty operations of the '50s. What can we expect from asphalt plants in the next 20 years?

Keeping it dry

Dr. J Don Brock, chairman of Astec Industries, and Dennis Hunt, senior vice president of Gencor, agree that asphalt plants of tomorrow will most likely be enclosed in a building. "There are some plants both in the U.S. and internationally that are already doing this," says Hunt.

Besides keeping the plant "out of sight" from neighbors, the covered buildings will help keep aggregates drier. The drier the material is going in, the less fuel you will use drying it, which translates into energy savings.

"Covering aggregates will become more popular," says Hunt. "You'll see more of aggregates in containers that help leech moisture out."

The use of recycled materials – reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) and recycled asphalt shingles (RAS) will increase significantly in the coming years. These materials will also be stored in a building as well as crushed inside a building.

"Seeing 60 to 70 percent recycle will not be uncommon, and an indirect tube type dryer will be used to preheat the recycle prior to its entering a plant," says Brock.

"Over the next 20 years, I see a substantial increase in both fuel for drying and the cost of the liquid asphalt," he continues. "That will lead to the need to store the aggregate in a building to keep it as dry as possible; paving the inside of the building with slopes to drain away as much of the moisture contained in the material as possible, prior to picking it up with a loader or a loading facility. Most likely plants will have top loading capabilities, such as using a drag chain for pulling the driest material off of the top of the pile."

Power options

- Solar. Solar panels on the roofs of the building, including those covering the stockpiles, will be used to supply a portion of the electricity to run the plant, says Brock. "Solar mirrors will heat the hot oil," he says. "The asphalt storage tank acts as a battery absorbing the heat and overheating the asphalt in the tank when the sun is shining. Heat from the asphalt can then be used at night or on non-sunny days as heat is required. "In peak production, line electric power will be required to supplement the solar power, but the solar will be sold back to the system when the plant is not running; thus making it a zero cost to the owner," he says.

- The best fuel? To remain competitive, higher percentages of recycle will be mandatory in the future, and the least expensive fuel to keep aggregates dry will have to be used. "I expect to see the plants being fired with natural gas since it will most likely be the most economical fuel available," says Brock. "If natural gas is not available, most likely wood would be used; also wood may be used if it is required to meet renewable requirements." Whatever fuel is the most economical will be chosen. "If you're next to a landfill, you can run the plant off methane," says Hunt. "Biomass fuel burners are another option. Anything with a caloric value we can burn can be used as fuel. We've made biomass fuel burners before, and they could become popular again," he notes. "And there are plants utilizing methane right now as well."

The future is now

We've come a long way from noisy, dirty, dusty asphalt plants.. Right now, say both Brock and Hunt, you can stand beside an asphalt plant and not hear the plant. "You hear the chains and conveyors but not the plant itself," says Hunt.

"Through using the latest technology available, plants today can be run at levels as low as 83-84 decibels, which is extremely quiet." Brock says.

You really can't smell an asphalt plant these days either. "Plants in California don't smell," says Hunt. "We have load-out tunnels, and we collect the fumes, which are incinerated or go through a filtering system. You don't see anything, and you don't smell anything."

With the warm mix foamed asphalt systems, smell is eliminated from the plant other than the loading of trucks into the asphalt storage facility. "By using a closed loop system to catch the air coming out of the tanks as they are filled and dumping them back into the transports, smell on the liquid side can also be eliminated," says Brock.

Tomorrow's asphalt production facility will be nearly invisible to the outsider. More precise controls and better automation systems will help control quality and efficiencies.