Incentives—rewards meant to encourage and motivate employees to be more productive—all too often backfire and create unintended consequences: internal squabbles, cynicism, distraction, and diminished performance. However, when used correctly, they can produce wonderful results. The trick with incentives is avoiding the pitfalls and common myths.

Following are the four most common myths regarding incentives:

MYTH 1: Incentives should be focused only on what a person can control

While this makes sense on face value, it ignores a huge factor in motivation: peer pressure. Many managers and contractors think that a person needs to have full and complete control in order for an incentive to be effective, but this just isn’t the case. You can create a very quick and dramatic improvement in your company with the use of a peer-based incentive program.

For example, an entire division or company can share in a bonus (e.g., when everyone comes to work on time all week, the entire company gets free coffee and donuts the following week.) Think about the corporate world where stock options are awarded to employees as incentives, and yet the entire company has to perform in order for the stock value to rise.

Peer-based incentives can be used to create change in many different areas: getting crews out on time, reducing equipment loss and vehicle damage, improving client retention. You should not have a problem with your employees accepting this incentive as long as the rules are clear and as long as you clearly explain why the incentive is being applied companywide (or division wide) as opposed to individually. Treat your employees like adults and explain the reasons clear and simple, and you may be surprised at how well your employees will enjoy the peer-based approach.

MYTH 2: An incentive should be holistic

Some business owners try to wrap up all the critical success factors into an incentive, but this can be confusing to track and can send mixed signals to the incentive recipient.

For example, I recently worked with a contractor who thought up a comprehensive incentive for his office staff. It was very artful in engaging his office manager and addressing all the key aspects of her job, except that it was too complex; it covered too many facets of her job and thus made it hard to prioritize what was important. Incentives should be straightforward, easy to memorize, and easy to calculate. If your incentive recipient cannot wake up in the morning, remember his or her incentive, it is probably too complex.

MYTH 3: Incentives will create a change in behavior

This is not true. Unfortunately, managers often put incentives in place expecting them to be a silver bullet and magically fix all that ails their companies. The important truth is, an incentive is merely a mechanism for how you measure the change, i.e. the improvement. But, in order to motivate the change, you need to give employees consistent feedback, and engage them in discussions on how the company is performing as compared to goals. Your employees need to understand why the change is important. Throwing money at them is not a replacement for explaining why it is important to hit the goal. Incentives will not automatically create accountability.

Most employees want to do a good job, but they often lack the tools or understanding needed to do the job well.

An incentive is not meant to replace a job description and is also not meant to replace the company operations manuals or handbook.

MYTH 4: Incentives must pay out monetary rewards in order for employees to buy in

This myth further states that monetary rewards should be significant in order for employees to really care. Neither is true. I have seen incentives programs with no money at all attached to them work wonders.

Take, for example, a company with four crews, and imagine that these crews compete against each other each week to see who can finish the week most efficiently under budget. Each crew is rated on how well it performs compared to its budgeted time. The results are shared in percentages; for example, 100 percent means they met budget, 90 percent means they beat budget by 10 percent, and 105 percent means they were over budget by 5 percent. Whichever crew ends the week with the lowest percentage, wins.

In fact, when a company is setting up a monetary-based incentive program for the first time, it may make sense to do a dry run and execute it with no money attached. This will allow you to work the bugs out of the system, and then later, if you wish, to add a monetary reward.

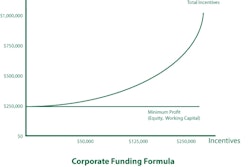

If you do create an incentive based on money, it should be self-funding. The incentive should be paid out based on incremental profits earned by the company based on the incremental results achieved. When incentives are self-funding, everyone wins.