For many, the traditional solution is to dispense lubricants and fluids right out of jugs, pails, kegs or drums. However, these methods present some issues, says Joe Murphy, president and general manager of Fireball Equipment Ltd. “For one thing, with drum storage, accurate inventory control is very difficult. Too often, the drum runs dry before a technician has dispensed the necessary amount of lubricant.

“Another frequent occurrence is that empty containers and drums often have residual product left in them. Over time, that amounts to a lot of wasted product.”

Drums take up a lot of valuable floor space and can be messy, Murphy says. There is also the chance that shop employees might hurt themselves when handling the drums.

There are alternatives to traditional packaged lubricants that “can provide an easier, safer, cleaner and more accurate and efficient way to handle all kinds of lubricants and other maintenance fluids,” he points out. These include centralized lubrication systems where lubricants can be stored in bulk containers and dispensed through hose reels right into the unit being serviced.

Management systems

“Without a fluid management system, it is difficult and time consuming for shops to track fluid changes in vehicles,” says Scott Hill, worldwide product marketing manager for Graco’s Petroleum Management Group. “These systems help record the date, technician, fluid type and amount dispensed into vehicles with relative ease.”

“Systems can dispense fluids, such as petroleum and synthetic oil products, transmission lube and antifreeze,” he says. “The systems provide access to data throughout the facility for automated tracking and monitoring, plus state-of-the-art dispensing for complete control of the fluid inventory.”

Fluid management technologies are evolving, notes Hill. “Older, wired systems can accurately meter oil and other fluids, but require technicians to walk to the parts counter where they make a request for the amount of fluids they need to dispense in their service bay. If the parts desk is busy with other orders or personnel are away from the desk, the technician must wait or come back later.

“In addition, many older systems only dispense fluids to one meter at a time. The technician might return to his workstation and have to wait his turn to dispense fluid.

“Neither one of these scenarios is an efficient use of the technicians time.”

Newer, wireless systems optimize technician time with systems that can provide accurate fluid inventory control, permit multiple fluids to be dispensed at the same time and allow the technicians to control the dispensing process at the service bay,” Hill says. These systems can also:

- Track vehicle fluids for more accurate and reliable metering and reporting.

- Track and maintain the correct level of fluid changeovers, from top-offs to complete fluid drains, and tie them back to the manufacturer’s recommended intervals.

- Support warranty claims with a complete history of fluid changes.

In addition, “wireless systems offer system installation and setup costs that are much less with far superior capabilities and flexibility over wired systems, he points out.

Eliminate waste

Len Badal, commercial sector manager, Chevron Lubricants, says “maintenance facilities can benefit greatly from an optimized storage and dispensing system for lubricants by preventing contamination, improving efficiency to deliver key lubricants at the right place, time and quantities and also help eliminate waste.”

Using programming dispensing equipment with meters can help manage the amount of lubricant that is dispensed to the working equipment, he says. “This helps eliminate waste from overfilling, and in the case of some products, such as grease, can help prevent damage.

“Overfilling cavities can lead to increased friction and heat or failed seals, which would then leak out grease causing lubrication starvation.”

Starting point

When deciding upon the appropriate storage, handling and dispensing equipment and system, a shop must first know what lubricants and fluids it uses, the amount of each being consumed and how much of each type is used in any given area, Murphy says. The shop also needs to consider the different fluid monitoring and inventory management and control systems available to manage and record the usage.

Typically, bulk storage tanks or tote setups can be used for high usage type lubricants - usually 200 gallons or more per month, Badal says. With lower usage type lubricants, packaging such as drums, kegs, pails, gallon jugs, etc., can be used based on a shop’s monthly or periodic requirements.

“However, some areas for low volume usage can be in mini-bulk systems or with the direction towards environmentally packaging offerings,” he notes. “Bag-in-the-box concepts are taking off for lower volume liquid lubricants.

“The bag-in-the-box concept has primarily been focused on passenger car engine oils and smaller volume items, such as automatic transmission fluid and gear oils, but can be extended to industrial and commercial lubricants to help lessen the impact of steel or plastic containers in the environment.”

Bulk products

When working with a shop to design and provide equipment configurations, one important piece of information Fireball Equipment gathers upfront is whether or not there is an advantage to using bulk lubricants delivered right to the vehicle rather than using packaged products.

“The answer falls into three categories: reduced product purchase costs, greater shop efficiency, and less waste,” Murphy explains. “The savings from bulk products varies significantly between suppliers and packaging types, and shop operations vary, so each fleet maintenance manager needs to do the math on their own.”

To assist in this undertaking, he offers this sample worksheet. While the example is for oil, the worksheet can be used for any fluid.

Bulk Product Worksheet

- Volume of product bought annually

- Savings per gallon

- Annual purchasing cost savings

- Number of oil changes per year

- Time saved per oil change (include time to get the packaged product, installation time and container disposal time)

- Value of annual time saved (hours per year x value per hour of bay time)

- Annual handling and disposal cost of packaging

- Annual value of retained fluid in packages

- Saving of prepaid disposal fees included in package purchase (typically $0.25/gallon)

- Total handling, waste and disposal costs

- Total annual saving from buying and handling in bulk

System strategy

When determining oil, lubricant and fluid storage, handling and dispensing needs, it is best to follow the fluid as it flows through the system and eventually gets recorded, advises Murphy of Fireball Equipment.

Storage - Product can be stored in kegs (15 gallons), drums (55 gallon), totes (portable tanks, typically 250 gallons in size) or tanks (typically 250 gallons and up).

“Our recommendation is to size the tank to a minimum of two months usage, keeping in mind minimum delivery sizes and price breaks,” he says. “Tanks are relatively cheap compared to what you might be able to save by buying quantities on sale.”

Lubricants have very high flash points - typically well over 400 degrees F - so they are not classified as “combustible” or “flammable” products, he points out. “As such, there are typically no fire code requirements for the tanks, including requirements for certification, venting or containment, but you should verify this with your local authority.”

Oil storage tanks have traditionally been steel, often the “oval” furnace oil tanks, but increasingly “we are seeing plastic because of aesthetics, cleanliness and product visibility. Larger steel tanks can be epoxy-lined to minimize contamination and rust.”

According to Murphy, if volumes don’t justify it, kegs or drums can be used instead of tanks. Kegs are typically put on a dolly and rolled right to the vehicle. “This works well for low-volume, high-value lubricants, such as synthetic gear oils, especially now that the new wireless control systems can record the dispensing of rolling kegs.”

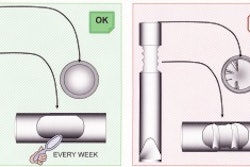

Drums are usually stationary and require an operator to switch over when empty. “This can be minimized by using a low-level cut-off to stop the pump when the drum is empty, and wall-mounting the pump so that a technician just has to move a stinger, and not the whole pump assembly,” he says.

“If the product that you need is not available in bulk, our suggestion is to install a tank anyway and transfer the product into the tank from the drum or tote. That way, you are not tying up space for containers and not changing drums partway through dispenses.

Pumps - Oil systems use air-powered pumps almost exclusively because they are simple, inexpensive and they can produce a variable flow rate and “stall out” under pressure, says Murphy. Automotive shops require about 2 gpm; heavy truck shops usually 3 to 4 gpm.

“In order to generate the pressure to deliver these flows, these pumps need to be a minimum of 5:1 ratio,” he explains. “That means that 100 psi of air pressure gets multiplied to 500 psi of fluid pressure.”

Hose Reels - “The ideal layout is to have one set of hose reels for every two bays,” Murphy recommends. Typically, hose reels are spring rewind and usually need to be 50 feet long to reach from the ceiling to the floor and then to the vehicle.

“Spring rewind reels can be as long as 75 feet if the bay layout permits it and you are willing to have hoses stretched out on the floor. Theoretically, a single 75-foot reel can cover a 17,000-square-foot shop.”

Dispense Valves - The “gun” on the end of the hose is available in a variety of configurations. These can range from an unmetered trigger, a metered valve to count the oil, a presettable metered valve that shuts off at a predetermined amount or a wireless controller that communicates back to a computer in the parts room that puts the dispense job on the work order.

Grease - Grease can be distributed to hose reels or supplied in one or two rolling kegs that supply the shop. Either way, Murphy says, they use a 50:1 ratio pump that delivers 5,000 psi pressure or more to the dispense valve.

“For this reason, it is critical that all hoses, especially the flex extension on the dispense valve, be rated for high pressure. Underrated grease flex extensions that fail after they get worn can cause serious grease injection injuries and are a significant safety issue in the industry.

“It takes less than 100 psi to inject a substance through human skin.”

He notes that there are systems, like the Graco Topper-Inductor grease pump system, that ensure all the grease is removed from a drum or keg, and include an air-elevator to help swap out drums without damaging the pump. “These are not practical for portables but we highly recommend them for stationary applications.”

Used Oil - Most fire codes classify used oil as a “combustible” product because it can contain amounts of fuel. For that reason, the typical tank needs to follow the local fire code, says Murphy.

“This likely will require a contained, certified, steel tank vented and equipped with an evacuation connection. It may also require mechanical protection from vehicle damage.”

Used oil is best transferred with a 1-inch air-powered double diaphragm pump, he says. This will evacuate from containers and drain trays at 5 to 10 gpm and will transfer it from the evacuation station to the storage tank.

“We do not recommend having a splash-fill location on the tank itself since this inevitably ends up as a cosmetic and environmental problem. Fill it with a pump and make sure you have some type of overfill protection to prevent spills.”

The size of tank is a function of how often the pick-up company needs to come and collect the used oil and what volume is generated.

Control Systems - Fluid monitoring and inventory management and control systems have evolved from the traditional console at the parts counter to hard-wired options and wireless systems that can put the dispense right on the work order, observes Murphy.

Traditional consoles sit at the part counter and require the technician to go there to order product, costing productivity, he says. Second generation systems have a keypad out in the shop to allow a technician to enter dispensing requests which increases efficiency. The keypad controls fluid using solenoid valves installed at the fluid outlets.

Third generation equipment is totally wireless and can tie into the shop’s in-house computer system, he says. There are systems than can simultaneously control, dispense and monitor numerous locations, are able to create reports by product, user, customer or location and monitor fluid stock levels.

Because they are not hard-wired, wireless control systems are a good option for retrofitting existing shops, plus they can handle portable dispensing equipment that wired systems cannot, he notes.

Product cleanliness

Proper storage, handling and dispensing guidelines are critical to ensure product cleanliness and performance in all types of equipment and all types of storage units, stresses Badal. “Improperly stored and handled lubricants can cause cleanliness issues and contamination, and that impacts equipment performance and useful life.”

Always ensure that dispensing lines and equipment are clean and that lines are periodically checked, and even purged, to make certain contaminants are not built up over time, or in the case of grease, that the thickeners don’t “harden” and block appropriate dispensing, he advises. Furthermore, in the case of changing lubricants, always clean storage and dispensing equipment to eliminate contamination or incompatibility, which will lead to equipment performance issues or damage.

The proper care and use of grease guns or keg/pail top dispensing units, is also important, as is keeping them clean and free of dirt or old grease to ensure correct application, he adds.

Frequently, the dispensing nozzle can end up on the floor or ground where it can pick up contaminants that could get inputted to a grease cavity, and causes problem. “Always be sure to store these nozzles properly and wipe them off before pumping in grease to the lubricated parts.”

It is best to “deal with lubricant suppliers that provide consistent quality of product and blending process to ensure all OEM specifications are maintained and product integrity is not compromised,” Badal says. “This becomes critical when any failures occur to ensure that warranties are covered and support is required for customer claims.

“Typically customers don’t realize the amount of testing required to maintain OEM approvals for quality products and some of the detriments to performance when short cuts are taken by less quality oriented suppliers. This can lead to costly failures and rejection of claims that can offset any savings in product prices.”

Selection criteria

To see if a fluid management system is right for your shop, Hill suggests contacting other shops using systems to get feedback on how their systems perform.

“Do some research to find out what the system features and benefits are so you can be certain it fits the needs of your maintenance department,” he suggests. “Contact a distributor to get an idea on cost, and realize that many systems can pay for themselves in less than one year.”

Regardless of the type of fluid storage, handling and dispensing equipment and system a shop decides upon, there are a variety of control systems available to ensure you have a record of the maintenance done on vehicles and all your fluids get billed out,” Murphy says. “From the tank to the control system, a well-designed lubrication system can make your technician’s work easier, save you money and increase the productivity of your maintenance shop.”