It seems like asphalt and concrete are always at odds with each other when it comes to our roadways. We can all agree that each material has its advantages and applications where it may be more beneficial than the other. However, concrete has long been preferred over asphalt for environmental reasons, but science is starting to see another side.

Urban Heat Island and Pavement

What has dominated the discussion about how concrete is better for the environment are the studies demonstrating how concrete has less effect on the urban heat island.

An urban heat island (UHI) is a metropolitan area that is significantly warmer than its surrounding rural areas. The main cause of the urban heat island is modification of the land surface by urban development which uses materials which effectively retain heat.

Since asphalt, the most common material used for pavement, is dark and has a low albedo (a measure of solar reflectance), it’s been said to generate more heat in urban areas and raise the temperature in these cities due to the material absorbing and retaining the heat from the sun.

Cement concrete is lighter, and thus has a higher reflectivity, and a higher reflectance is generally considered a positive as less heat is absorbed.

Total Pavement Cost

While some studies continue to argue that reflective pavement can reduce UHI effect, the embodied energy and emissions in some materials may present unexpected drawbacks, according to new research from the DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

We know that the extraction, production and transportation of pavement materials and the construction of pavement maintenance and rehabilitation treatments generate pollution and consume energy. Therefore, the team used lifecycle cost assessments (LCA) to see the total environmental impact, from cradle to project completion all the way to end of life, for each pavement material.

“The LCA provided a comprehensive evaluation of the environmental burdens from a product or service by quantifying the environmental effects of a product throughout its life cycle,” the study said. “In LCA, the inputs, such as energy and resource consumption, and outputs, such as pollution, are identified and inventoried over the product’s entire life cycle, which usually includes material production, material transport, construction, use and end-of-life.”

What the study found was that while cool pavements may provide environmental benefits that help cities meet their sustainability goals, switching pavement management practices can also change upstream environmental burdens.

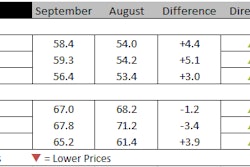

The energy and emissions associated with each pavement type’s materials and construction were paired with a regional climate model and simulated building energy consumption to determine the likely impact on buildings. The team was surprised to find that in most cases, the extra energy embodied in the cool material (concrete) far outweighed the energy savings from increasing the solar reflectivity. Concrete also requires a high-temperature process that is considerably more energy- and carbon-intensive than making asphalt from petroleum.

“Over the lifecycle of the pavement, the pavement material matters substantially more than the pavement reflectance,” Ronnen Levinson, a researcher in Berkeley Lab’s Heat Island Group says. “I was surprised to find that over 50 years, maintaining a reflective coating would require over six times as much energy as a slurry seal. The slurry seal is only rock and asphalt, which requires little energy to produce, while the reflective coating contains energy-intensive polymer.”

Recycling & Reuse

What the study did not mention was that asphalt is also the number one most recycled material in the United States, making it an even more attractive material for locations concerned about sustainability and the environment.

A wide range of waste materials are now incorporated into asphalt pavements, including ground tire rubber, slags, foundry sand, glass and even pig manure, but the most widely used are reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) and recycled asphalt shingles (RAS). The use of recycled materials in asphalt pavements saves about 50 million cubic yards of landfill space each year.

While the research and reasoning on what material to use is continuing to evolve, with asphalt leading the way as the most cost-effective and easy to produce material, state and local governments should be hard pressed to use anything else on our roads.

You can read the full study at https://heatisland.lbl.gov/sites/all/files/e-b-cool-pavement-campaign.pdf