Smoothness on a paving job is king. There are many ways to achieve smoothness and the use of technology is one of them. Most paving contractors are familiar with 3D paving which refers to the three dimensions of depth, width and direction of paving. The big benefits of using 3D are providing exact levels of smoothness, accuracy and material management.

“If a contractor has made the decision to 3D pave, it would mean they are trying to achieve a desired elevation or a desired top surface of the pavement that is as smooth as possible for International Roughness Index (IRI) and smoothness bonuses and incentives,” says Kevin Garcia, business area manager for paving and specialty construction in Trimble’s Civil Engineering and Construction Division.

When your underlying surface isn’t smooth to begin with however, variable depth paving – or uncompacted design using 3D elements, may be beneficial.

“When you pave on top of an already relatively smooth surface, that’s pretty easy. All you’re doing is managing thickness at that point,” Garcia says. “Uncompacted design, or variable depth paving, allows for a smooth final surface even if the underlying surfaces aren't smooth to begin with.”

All About That Base

We know that a pavement is only as good as the base that it’s put down on, and while some contractors have made the leap into 3D paving, they may not be getting the full benefit of the technology by adding 3D grading and milling into their paving programs.

“In many cases, the contractor in charge of doing the grading and the milling is not in charge of doing the paving so there is no real incentive for them to make sure that surface is perfectly prepped for the asphalt contractor,” Garcia says.

Asphalt contractors then can be left with a surface that is not prepared to the high accuracy they may need. This is especially an issue when the compaction factor is considered.

“Asphalt pavers are really really good at paving things smooth. They are great at holding the screed flat and filling in any low spots as they go over them so you get what looks like a perfectly smooth surface after paving,” Garcia says. “However, if you have a base profile that goes from 3-in. to 6-in. down to 2-in. and so on, the compaction factor is going to be different in those low spots. You’re going to get more compression where you placed more asphalt and less compression where less asphalt was placed.”

Typically, paving removes between 70-80% of low spot deflection with each pass so you may be able to smooth a low spot out relatively well before the finishing layer, but compaction will always cause some form of longitudinal waving.

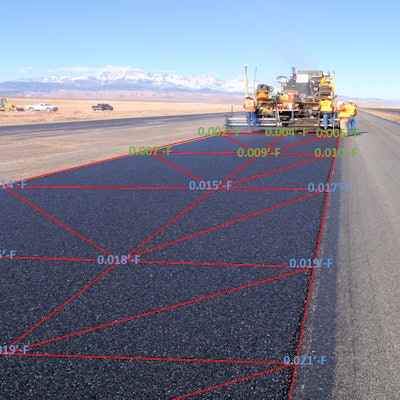

Uncompacted design on the other hand, takes into account the surveyed surface of the original base prior to paving.

“With this technology, we pave higher in some areas and lower in others on purpose, specific to a 3D design,” Garcia says. “We design these jobs with accurate topography of the surface, accounting for the compaction factor of the asphalt after it's rolled...thus the ‘uncompacted design.’”

Garcia says the compaction factor of the asphalt being used for the project is typically provided by the QC lab of the contractor and it can change with each job. The compaction factor for each mix can change based on the gradation in the mix, the oil that’s used and even the amount of time the mix has to travel to the paving site. It’s not always a ¼-in. per inch.

“Then with a few other proprietary parameters, we create a 3D surface in our design software for the paver to execute against,” Garcia says. “The paver will adjust the screed per the design, giving a little more asphalt in certain areas. The results are a smoother surface with less effort.”

Garcia says that for some contractors, this type of paving is a huge leap of faith.

“They are very used to looking behind the screed and seeing a very smooth, very flat mat and that’s their idea of a quality job, not thinking the underlying surface may change considerably,” Garcia says. “Now, we’re paving waves on purpose. Even though the mat may not look smooth as it leaves the paver, we know that we’ve accounted for the void space and air voids in the mix and how much it will compress once the roller hits it to leave us with a smooth surface in just one pass.”

Why Implement Uncompacted Design?

If you’re already doing 3D paving, uncompacted design is not a large jump to make. There’s no new equipment to buy, you just need to make changes in how you build the design in your software business center and making that change can save you big money.

“In most paving applications, we're prioritizing several factors including minimizing material usage and smoothness of the final surface,” Garcia says. “If you are paving a fixed depth on a surface that has a lot of longitudinal waves, it's very difficult to take out those waves, even with an averaging beam on the paver, which is designed to help with that. If the underlying surface has longitudinal waves and we simply pave a fixed depth, we end up with the same waves, only at a higher elevation. The most commonly used method to get rid of those waves is to first pave a leveling course before finishing paving. With the uncompacted design, we can eliminate the need for a leveling course and pave a smooth final surface, removing an entire step from the job.”

And eliminating an entire layer of asphalt equals big money saved.

“When budgeting a job, most contractors are planning to run over on material so they factor in about a 3% overage on their yields,” Garcia says. “We worked with one company that was going to incur liquidated damage costs of $240,000 for every day they went over on an airport project. Had they not used 3D, they would have missed the deadline by a minimum of 10 days, costing them over $2.4 million.

“With the technology, they were actually able to finish three days early,” Garcia continues. “And since they knew exactly what they were going to be placing, they used 1,000 tons less material than they intended and were able to put all those production and material costs right back in their pocket.”

In addition to achieving smoothness bonuses on bridge decks and specialty projects like race tracks, many DOT’s are starting to place a larger emphasis on IRI’s.

“Many DOTs have IRI specifications and if the road you’re starting with is running a 150-160 IRI and you’re expected to get it down to a 75, you’re either going to have to employ multiple leveling courses across the road which are time consuming and expensive, or you can use uncompacted design and 3D paving,” Garcia says.

And while Garcia says the adoption of the technology is relatively low in comparison to the opportunities it presents, contractors who have implemented it have seen great success saving both time and dollars.

“The barrier to entry costs on these systems has come down considerably and what we find is that once you’ve paved three miles, you’ve paid for this system and then some,” Garcia says. “The technology that goes on the machine hasn’t changed in price much, but contractors don’t necessarily have to buy the total stations anymore, they can rent them out and return them as needed and significantly bring down that initial purchase price.”

Garcia says that it’s still surprising how many contractors have not even heard about this type of technology and are not aware of the opportunities it can present to them. Contractors may soon get a trial by fire as many DOT’s will require 3D paving on some jobs and that’s money you can’t afford to miss.

“True 3D paving has been available since 2009 and the guys that were early adopters are winning more bids, making more money and their competitors are starting to notice. Contractors are starting to see the value of this, are less intimidated by the technology, and the benefits to their business are just going to grow once implemented,” Garcia says.

“We’re just starting to scratch the surface of what this technology can do,” he concludes. “We’re going to see contractors use this technology in new and unique ways, linking machines so we can start sharing productivity data. We could see tonnages placed per hour, number of machine stops per hour and why, and theoretical smoothness numbers directly out of the machine in real time.”