A public library is a symbol of equality and opportunity. Its doors are open to everyone; its contents free to all who want to learn. Many major cities across the United States count their public libraries as a centerpiece to their architectural character, and for many people a visit to the library may be their first introduction to architecture. The new San Diego Central Library is an example of one of these inspirational architectural centerpieces completely accessible to the public.

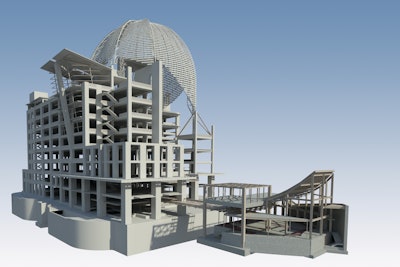

The 504,000-square-foot building includes two levels of underground parking and nine above-ground occupied floors to house 1.25 million books, more than 400 public computers, meeting rooms, study areas, gallery space, a 400-student charter school on two floors, central offices to serve the 35-branch library system, and a nearly 4,000-square-foot reading room enclosed with three-story-high concrete, glass and steel walls. The library building includes 28,000 cubic yards of structural, cast-in-place architectural concrete and an additional 15,000 cubic yards of non-architectural structural concrete.

Concrete work on the building is just winding down, and the new library will open to the public in July 2013. Concrete subcontractor on the project was Morley Construction Company’s concrete group out of San Diego, Calif. Morley spent nearly 18 months on site, averaging about 70 employees on the job throughout the construction.

The project is an epic accomplishment in concrete construction. Unique elements include roof cantilevers exceeding 11 feet, hybrid structural systems, 6-foot-square and larger mass concrete columns, and a 46-foot-tall and 70-foot-wide concrete gravity arch. “Even the guys who have been at Morley a long time refer to it as a landmark project in their careers,” shares Sean Fleming, project manager with Morley Construction Company. “It will be an iconic structure for the city, and its domed silhouette is sure to become a signature of the San Diego skyline.”

Getting the job

Planning for the new library began in 1995, when the city of San Diego began earmarking the funds it needed to replace its 1950s-era main library to serve the city’s growing population. The city hired architect Rob Wellington Quigley to design a building that would serve not only as a shelter for books but a community gathering space and architectural focal point for the downtown area. Over the next 15 years the city raised the $185 million needed for construction while plans were completed and permitted. In 2010 Turner was hired on as general contractor and initiated the bidding process for a concrete subcontractor and other trades.

Turner utilized a best value bidding process to award all trades in the public bid. Morley was one of eight prequalified concrete subcontractors to submit a proposal. Different aspects of the project bid were weighed, including 50 percent for price, 15 percent for relative experience and 5 percent each for contractor financial standing, bendability, claims history, EMR rating, small business and local participation, and management team experience. “Morley’s combination of competitive pricing and high marks in team experience, safety record and small business partnering secured the award,” Fleming says.

An open structure

The library was structurally designed to provide open floor plans throughout the building with lots of natural daylighting. “As you walk the floors of the library, for instance through where the stacks will be, there is very little interruption of the space,” Fleming says. “Even though you’re in this expansive concrete structure, what might appear imposing on the plans is in fact open and airy.”

This open effect was achieved through the use of Special Moment-Resisting Frame (SMRF) concrete beams and columns incorporated with conventional waffle slab floor plates, which all but eliminated the need for shear walls throughout the building. Typical SMRF beams are upturned 5 feet deep by 27 inches wide, while the SMRF columns range in size, up to 75 inches square. The SMRF beams and columns are located along the structure’s perimeter to create rigidity in the planes of the building facades. This design strategy allows the interior of the library to be supported by much smaller gravity columns, only 30 inches square.

The floors are constructed of 23-inch-thick waffle slabs with waffle voids spaced 4-foot on center. Voided slabs allow for wider spans between columns; on the San Diego library project, bays spanned 32-feet on center. Further contributing to the streamlined design are the use of in-slab beams, which combined with the aforementioned upturned SMRF beams greatly reduces the occasion of traditional down-turned beams.

Special features

The building contains a number of unique concrete features. Acting as a focal point of the building interior, spanning through the main lobby with an escalator moving vertically through it, is a 46-foot-tall and 70-foot-wide concrete gravity arch. It requires no mechanical connections for its function of supporting the loads of the five stories above it. Morley considered a multitude of forming scenarios and conducted in-house peer reviews of three “finalists” before settling on a combination of Peri Vario wall forms, GRV Radius Forms and Multi-Flex shoring.

The eighth floor reading room has a 60-foot-high ceiling with walls of steel and glass. The structure resembles a lantern and allows for natural daylighting. Supporting the structure are four 6-foot-square columns arranged in a cruciform plan and centered on each wall to create the structure for the diamond-shaped, cast-in-place concrete, steel and glass roof. The beams that support the roof span 58 feet clear in both directions. Peri Multi-Flex shoring towers were used to shore the roof deck and beams. Covering the reading room is the freestanding, dome-shaped sun shade constructed of a series of eight rib trusses and sails arranged in a scalloped formation, overlaid with fixed perforated steel lattice work.

On the building’s west side, offering views of San Diego Bay, is the ninth floor, 400-capacity Special Events Room. The room’s hybrid roof structure cantilevers 20 feet beyond the west façade supported at center-bay of the overhang by a single 4-foot by 6-foot inclined concrete column leaning out at a 10 degree pitch originating at the fourth floor 90 feet below and culminating 30 feet above the ninth floor. The column supports two precast “Grand Beams” that are arranged in a pitched V-shape, each tied in to a 60-foot spanning beam wall at the room’s eastern side. A series of 20 precast purlins, four tube steel columns and other steel beam work interface with cast-in-place architectural concrete roof slab and perimeter beam to support the roof. The roof slab is designed with non-linear cambers of varying degree that require Morley to install shaped falsework to affect the sculptural condition. To achieve the extreme loads and cantilever condition Morley hired RMD Kwikform who designed a series of custom megatrusses and outriggers to support Superslim and Alshor deck shoring.

The library also features the circular-shaped Commission Room, created by what Fleming calls a “miniature modern effigy of Stonehenge” made up of 12 H-shaped concrete columns arranged uniformly in a circle. Each column has a “bent” center so it is not a true H in plan. Further complicating the columns, the “web” of the H changes in width several times or disappears entirely along their 33-foot height. Atlas also supplied these column forms utilizing a two-piece column form gusseted with shaped plywood and lumber fillers to create the necessary shapes.

In total Morley hired six formwork vendors to answer the challenges of the project. Custom structures such as the gravity arch, Commission Room column forms and Special Events Roof were unprecedented for Morley and its vendors. Close collaboration with the vendors’ engineering teams were necessary to find the best approach relative to constructability while maintaining sensitivity to the architectural aesthetic. Fleming notes such an approach is vital to good architectural concrete practice, but that such collaborative efforts are common on all Morley projects, not just with vendors but with all who have a stake in the project. “We staff most every job with a full-time engineer and superintendent, often safety engineer and project manager too,” he says. “We find that taking a collaborative, proactive approach at every level of involvement results in superior products, happier clients, and improved bottom lines, even with hard bid public work.”

Forming patterns

One of the aspects of the library project that required a high level of planning on Morley’s part was achieving the architect’s vision for the architectural concrete. He wanted the color to be light and consistent with minimal mottling, a matte finish, minimal read of plywood grain and surface imperfections, and minimal tie holes. Another feature he asked for was a readily visible random pattern and non-repeating plywood design, referring to a “collage” or “quilted” effect that added texture and context for the building.

Morley designed random plywood patterns for every column form including the various “block-out kits” inset within the column forms to create T- and L-shaped columns. Also employing the random pattern design requirement were the walls, exterior beams, exposed decks and concrete gravity arch. Plywood sheets were cut to 4x4 and 3x6 or smaller and arranged to create a random pattern. “It was a request we had never done before and many thought it couldn’t be done. I took it as a challenge and personally designed nearly every pattern you see on the job. I started with the columns and walls and moved on to the gravity arch. The end result truly looks random, but it all had to be preplanned,” Fleming says. “We came up with elaborate coding plans for the plywood layouts, almost like a paint-by-number drawing, to identify pieces so they could be pre-cut and assembled in the correct order on the jobsite.”

Because this project had a large number of column types, Fleming created a column numbering system and floor-by-floor column placing plan to streamline the column forming process. “One column form could be responsible for creating six different shapes, so we had to minimize the handling,” he says. Every column type was coded by color and given a designation by letter and sometimes number as well to identify the shape and any kits required to modify the shapes. The forming crews then had precise direction on column placement order. Since column forms were to be reused from bay to bay, instructions were given specifying the orientations the column was to be turned to achieve an even higher degree of randomness.

The forms were all double-layered plywood and backscrewed, or finish nailed, with the first layer a shop-grade and the fascia layer being Olympic Panel’s Barrier Film, a white malamine overlaid plywood. “There was no water absorption into the face of the panel so it gave us a bright color when compared side-by-side with other architectural-grade plywood products,” Fleming says about the decision to use the Barrier Film product.

Morley pushed the boundaries on the tie hole pattern in the columns, too. With 15-foot spacing between the floors and the architect’s request for a uniform appearance in the tie pattern, Morley needed spacing that would be divisible by 15. Three-foot spacing was too tight for the architect, so they pushed form tie spacing to 5 feet on center. “We challenged a lot of our vendors with that request, but we found ways to make it work, such as increasing the size and reducing spacing of walers and utilizing lots of dry ties. In the case of SMRF columns, Atlas utilized 4x4 walers spaced 8 inches on center with their 5-inch, multi-channel column clamps spaced 12 inches on center then paired a full-height aluminum strongback down the center,” Fleming says.

Morley crews applied the same random pattern styling to exposed beams, walls and the gravity arch. “Getting the random pattern in the arch was challenging because we were working with square seams in a curved form and had to figure out how to line up tie holes and keep them at least 12 inches from a seam,” Fleming explains.

The result was worth the effort. “It really is a special effect of sorts when you look at it,” Fleming says. “With so much of the architectural concrete in the world today you can immediately see a distinct pattern in the tie holes, lines and seams, and your eye automatically follows those manmade patterns. But because this building has so many random seams everywhere, when you look at it your eye moves constantly. Rather than appearing mechanical, it looks organic.”

As the concrete work on the library project winds down, it’s evident that the architect’s vision for a structure that will serve as a centerpiece to the city’s character and community activity has come to life. And it’s a building that embraces its construction and materials.

“The design allows for everyone to see the way the building is built, that is to say that the materials used to build it and various components used to make the building run and function are visibly expressed, not hidden. It’s honest to the trades, and being builders we can really appreciate that,” Fleming says. That means exposed steel, exposed mechanicals and of course the design and structural elements composed of concrete both inside and out. It proves the San Diego Central Library is not only a centerpiece for the city, but it is also a concrete structure that serves as an example of the opportunities cast-in-place concrete can offer the architectural design community.