This will be no ordinary interest rate cut, writes the New York Times’ Neil Irwin.

The Federal Reserve is planning to cut rates at its policy meeting at the end of the month even though the United States economy, by most available evidence, is doing perfectly fine.

Late May and June brought a weak report on the labor market, a plunge in some surveys of business activity, and market volatility as traders bet on Fed rate cuts. It looked like the first stage of a major downturn.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell essentially confirmed that lower rates were on the way in his mid-June news conference and subsequent public appearances.

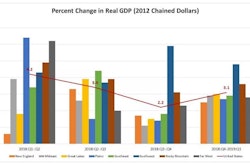

But in the last few weeks, the economic weakness has come to look more like a short-term blip than a trend. The job market is quite healthy by any modern standard, according to the latest numbers, and overall growth for the quarter that just ended looks likely to be comfortably in positive territory. American consumers keep spending money, a reality confirmed by a good June retail sales number released this week.

The Wall Street Journal points to recent reports indicating U.S. economic strength:

- Retail sales rose 0.4% in June from May, exceeding economists’ 0.1% forecast

- Consumer spending looks to have grown 4.3% in the second quarter, the fastest pace since 2014

- Manufacturing output increased by 0.4% in June from May

Throw in the strong June jobs report (unemployment is near a 50-year low), the recent detente on trade between the U.S. and China and a stock market that has lately reached new records, and it is a little hard to remember what the Fed’s fuss was about.

Powell has had opportunities to back away from the rate cut message, including in congressional testimony and a speech in Paris. He did not do so.

Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren told CNBC that he is not on-board with a July rate cut. He joins Kansas City Fed President Esther George as the only two voters on the Fed’s Open Market Committee who have publicly stated they don’t see the need for a cut, at least not yet.

“So, given that the economy is quite strong, given that I do think that inflation is going to be very close to 2%, and given that the growth in the economy is satisfactory, I think that’s an environment where you don’t have to take a lot of action,” he told CNBC’s Sara Eisen during a “Closing Bell ” interview.

“Now, should the economy change, if the trade situation changes dramatically, if we start getting surprised by how slow China or Europe are, then that’s something we definitely should react to. But I think we should wait until we actually see the evidence that that’s happening,” Rosengren added.

Market participants and some Fed officials, particularly St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, have cited the need for an “insurance” cut to serve as a buffer against potential weakness. Such a move also would offset the December rate increase, which has been criticized harshly by President Donald Trump, who took a few more shots against the Fed in a series of tweets Friday.

Rosengren said such an insurance move comes with costs, and might be particularly risky considering how high the stock market has soared and the surging levels of corporate debt.

A cut now could fuel financial bubbles that eventually put the expansion at risk.

History tells us that the stock market's reaction to rate cut hopes are playing out as they did the last two times the Fed did this. That was at the end of the year 2000, and in the second half of 2007. Both turned out to be just around the time the S&P 500 stock index went from teetering near an all-time high, to falling over and destroying wealth. We all need to be aware that a rate cut now or soon is more likely an admission that the economy is indeed falling over.

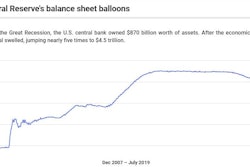

A short-term immediate risk for the Fed in cutting rates now is that it could limit the central bank’s arsenal in fighting the next economic downturn. The Fed’s main benchmark rate is less than 2.5%, low by historical standards, leaving little room to decrease rates further to stimulate a flagging economy.

A more-incessant challenge to Powell’s decision, more so even than global uncertainty, is likely to come from the Oval Office. President Trump has been publicly hammering Powell to lower interest rates; hammering as hard as he pushed for higher rates during the nascent recovery of the Obama years. Trump has criticized the Fed for raising rates four times last year and no one thinks he will be satisfied if the Fed drops its benchmark rate by a quarter point on July 31.

Trump and his economic team have pressed the Fed to slash rates by a full point, and Trump isn’t likely to stop jawboning in the coming months.

The administration’s sense of rate-cutting urgency and severity appears incongruent in a context of record employment and stock market performance, until you consider the effect of Republicans’ 2017 Tax Cuts & Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA). The U.S. Treasury Department’s report on the 2018 Federal budget showed that corporate income tax receipts fell 31%, or $92 billion. It was the second-largest decline in corporate income tax receipts on record, behind only the 55% plunge from 2008 to 2009.

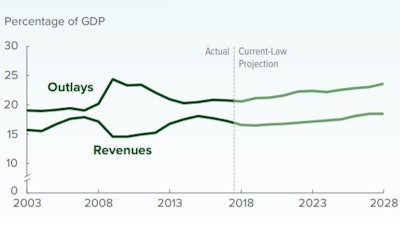

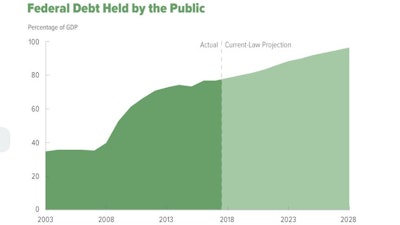

In 2018, the Congressional Budget Office updated its conventional forecast of how much the TCJA will increase the Federal deficit, expecting nearly $2.3 trillion more debt over its first decade. To finance the TCJA’s cuts, the government will issue additional Treasury securities and pay additional debt service. Half or three quarters of a point on interest rates will significantly impinge on the government’s capacity to borrow money in response to a downturn.

Some economic experts say Trump already has succeeded in getting into the heads of Fed decision makers.

“Powell does seem to be going a little bit out of his way to reverse the rate hikes made last year,” said Chris Rupkey, managing director and chief economist at MUFG Union Bank in New York. “The president’s like another active member of the Fed board in the room. I wouldn’t tell him no, would you?” The federal budget deficit rises substantially after the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act of 2017, boosting federal debt to nearly 100% of GDP by 2028, despite CBO projections for relatively quick economic growth in 2018 and 20019.Congressional Budget Office

The federal budget deficit rises substantially after the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act of 2017, boosting federal debt to nearly 100% of GDP by 2028, despite CBO projections for relatively quick economic growth in 2018 and 20019.Congressional Budget Office