The Federal Reserve on Wednesday cut the benchmark federal funds interest rate for the first time in more than a decade, even as the U.S. economic expansion reaches record length, unemployment hovers at historic lows and consumers keep spending.

According to the New York Times, uncertainty around global growth and persistently low inflation are behind the expected move, because both pose major threats to the health of the economy at a time when the central bank has limited ammunition to fight off a downturn.

The quarter-point cut, to about 2.25%, is what’s called an “insurance cut” — one that central bankers are making to keep growth chugging along.

The Los Angeles Times reports that the Fed statement signaled that the central bank was prepared to cut rates further, reiterating that it “will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion.”

That strategy is a departure from the past when the central bank typically acted only after seeing actual evidence of an impending downturn.

The danger is that interest rates are already low, and dropping them further not only nicks the Fed’s firepower when a real downturn comes but also could add fuel to stocks and other assets that are at very high levels.

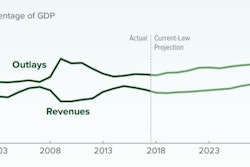

The Washington Post reports that, in addition to the rate reduction, the Fed announced that it would stop selling off its $3.8 trillion in assets in August, two months earlier than expected and another easing move.

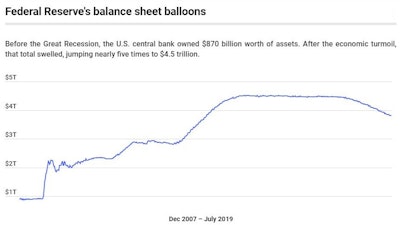

Bankrate.com explains that as last-decade’s financial crisis worsened and interest rates slashed to virtually zero failed to revive the economy, the Fed decided to do more. It started to buy massive amounts of bonds, including “subprime” mortgage securities and other forms of distressed debt, listing them as “assets” on its balance sheet.

The Fed reasoned that their buying would support those instruments’ prices, and sellers of these securities (such as big banks) would use the cash from the sales to boost lending and reinvest in their businesses.

In August 2007, before the financial crisis hit, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet totaled about $870 billion. By January 2015 its balance sheet had swelled to $4.5 trillion; more than a five-fold increase. The Fed began reducing its fixed-income holdings in October 2017, and its balance sheet as of July 15, 2019, was $3.808 trillion.