The diesel engine traces its roots back to the late 1800s. Rudolph Diesel developed a compression ignition engine that ran on peanut oil, but it was the economics of the oil rush that created the current diesel fuel infrastructure.

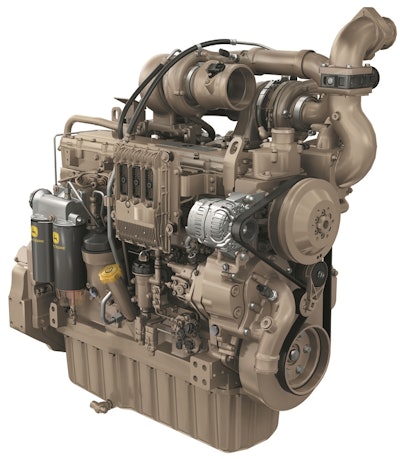

Over the past 50 years that Equipment Today has been published, the evolution of the diesel engine has progressed from a crawl to an outright run. Diesel engines have greatly increased in power density with similar-sized engines pumping out incredible horsepower and torque vs. their early counterparts.

Much of this is due to tighter tolerances and improvements in fuel injection technology. Fuel injection is arguably the most important and most complex part of a diesel engine. Nobody 50 years ago would have believed a fuel injection system could produce 44,000 psi and multiple injection events per cycle and still live for thousands of hours. This is a key enabler to performance and meeting emissions standards.

50 Years of Construction Equipment History: Interactive Timeline

Early Evolution

Off-road diesel engine technology evolved slowly through the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s with a steady increase in power density and gradual weight reduction. “There is a fairly consistent trend to greater power density, smaller engine size for the same amount of power,” notes Rich Winsor, senior staff engineer, John Deere Power Systems.

One of the first major advancements during the late ’60s and into the ’70s was turbocharging. “We were trying to get more power out of a small displacement,” says Doug Laudick, product planning manager, John Deere Power Systems. Related to turbocharging, charge air cooling was another technology that emerged to squeeze more power and efficiency out of a small displacement package. The air from the turbocharger could be cooled before it entered the engine.

Charge air cooling was also a key to increased durability. “Otherwise, if you increased the power the engine would not live,” says Winsor.

Similarly, fuel injection pressure plays a critical role in off-road diesel engine performance. For this reason, fuel injection pressure has always been a focus and it was increasing long before the introduction of electronics. “There was a lot of work to continue to increase injection pressure,” says Winsor. “Basically, it improves the combustion, which improves the engine efficiencies and also reduces the smoke.”

Emissions Standards Transform the Landscape

The pace of change in the off-road diesel engine industry changed dramatically when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published the first in a series of off-road diesel engine emissions regulations.

The off-road diesel engine emissions journey began in 1996 with the introduction of Tier 1 emissions standards for engines above 175 hp. But the first couple tiers of regulation merely accelerated improvements that were already occurring in the market.

“There weren’t major advancements at that point other than the engines were continuing to advance because of higher injection pressures, more turbocharging and more air-to-air charge-air cooling,” says Laudick. No real technological breakthroughs were required.

This was about to change as the subsequent emissions levels established more draconian limits. “Tier 3 was a little more of a challenge,” recalls Laudick. That is where some companies took different approaches, with some de-tuning engines and others adopting cooled exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), a new technology for the off-road market.

“The use of cooled EGR allowed us to improve our power density and performance,” says Laudick. “We saw some pretty substantial gains in fluid economy.” The difference in fuel economy between the different technology approaches became more of a factor for customers. “When you get 10% to 12% difference in fuel economy, that starts to get the customer’s attention.”

In this timeframe, probably the most significant single change to the diesel engine occurred — the advent of electronic controls. Electronic fuel injection was a game changer for the construction equipment industry. Fuel injection technology has leaped forward with a move toward common rail fuel injection that allows higher pressures and piezo fuel injectors that produce exact spray patterns.

Electronic engine capability has set off the march of electronics. “We have engine management systems and transmission management systems now,” says John Patterson, former CEO and president of JCB. “We have the introduction of software that manages the entire powertrain, all to improve the performance and the efficiency, as well.”

“Without a doubt, all of the electronics that have gone into the machine have allowed us to do an awful lot of things to customize that machine for that job and that customer’s requirements,” says Brian Rauch, senior vice president of engineering, manufacturing and supply management, Deere & Company. The engine now communicates with other systems on the equipment. “We have a lot more controllability built into the product. The challenge is to make it automatic. We want the operator to manage the dirt, not the machine.”

The engine and machine systems can now be integrated to a level not previously imagined. “We have integrated the hardware and software,” says Winsor. “The engine talks to the transmission. That is fairly recent.”

With the electronic engine capability, manufacturers began to ask themselves what additional features could be added to the machines. “This is where you started getting auto idle, dial throttles and advanced hydraulic systems,” notes Katie Pullen, Case Construction Equipment. The capabilities have moved beyond diagnostic capability. “Manufacturers are really being tasked to integrate machine control and different site solutions into their machines.”

As diesel engines have become part of an integrated machine design, many OEMs have moved toward captive engines so they can offer engineered solutions. This includes companies such as JCB, which used to source engines and recently developed its own in-house solution. “There are very few independent OEM engine manufacturers left,” says Patterson. The theory is that by building key components in house, you are able to optimize the system with fewer compromises.

Looking Toward the Future

In the past, a diesel engine was primarily used to power the equipment’s powertrain and hydraulic systems. But manufacturers have begun to introduce hybrids and electrification in the search for efficiency gains. In some cases, the diesel engine serves a different purpose — for example, it may run in a steady-state condition to power a generator.

Despite all the talk of hybrids and electrification, don’t expect the diesel engine to go away anytime soon. “Internal combustion engines are going to be around for some time, but they could be complimented by other forms of technology, such as hybrids. We are already seeing various versions of hybrids,” notes Patterson. “OEMs are working with component manufacturers to develop hybrid technology, including electrification. Regeneration, for example, is already here.”

A recent trend in the diesel engine business has been lower rated speed. “If you go back in time, some of our product ran at 2,300 or 2,400 rpm,” says Winsor. Today, some of the engines in construction equipment applications turn as slow as 1,800 or 1,900 rpm. “There are some real benefits to running slower from a performance perspective. It helps you improve fuel economy of an engine and it helps with the life of the engine because you turn fewer revolutions doing the same amount of work. There are also benefits in noise reduction. Any time you run the engine slower, it is going to be quieter.”

While there is talk of further particulate matter reductions with an anticipated Stage 5 in the future, most think this will be easily accomplished with the diesel particulate filter and no new technologies will be needed. The reduction in diesel engine emissions since their inception has been dramatic. “From the onset of regulations until now, we have reduced over 99% of the particulate matter, hydrocarbons and NOx from diesel engine emissions,” Rauch points out.

There could be a renewed focus on engine performance. “The focus over the last 20 years has been on emissions control,” says Winsor. “That is going to be a little bit of a change in the future. Emissions control will still be there, but I think the emphasis will be more on fuel efficiency, packaging and cost.”

50 years of construction-equipment history in an interactive timeline