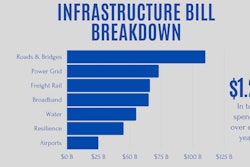

Once the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill was passed, Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer (D-NY) and Budget Committee chair Bernie Sanders (I-VT) agreed on a deal for a $3.5 trillion antipoverty and climate package that Democrats plan to pass through reconciliation.

The plan calls for the investments to be offset by a combination of new tax revenues, health care savings and long-term economic growth. It calls for raising money through IRS enforcement and proposes a new fee on carbon pollution. The plan prohibits tax increases on families making under $400,000 a year, small businesses and family farms.

Democrats won't get any GOP help to pass a $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill. But combined with the separate bipartisan package, it's expected to bring the total of new spending on "infrastructure" to $4.1 trillion.

Since it's passage in the Senate, various committees in the House have been writing up the proposals that the resolution outlines. Schumer set the goal for committees to write up the legislation by Sept. 15. Democrats can then start negotiating the bill within the 50-member caucus.

This does not give the House much time to finish the legislation and vote. To pass the pricey $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill, party leaders will have to keep Democrats almost entirely united to be able to use the reconciliation maneuver successfully which is already impossible with several in their party expressing concerns over the price tag.

This also complicates things for the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill as its passage rides on simultaneous passage of the reconciliation bill.

"No Infrastructure Bill Without Reconciliation"

The $3.5 trillion budget framework has been tied to the bipartisan infrastructure plan since early this year. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) insisted that the infrastructure bill would not be voted on until the Senate passed the broader spending plan. In the House, Democrats have a slim majority. Republicans will oppose the measure unanimously and argue the spending is irresponsible. In the Senate, Democrats must keep all 50 members together, including centrists who have already balked at the $3.5 trillion price tag.

Joe Manchin (D-WV) has been vocal in expressing his concerns over the reconciliation package. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, Manchin called for Democrats to “hit a strategic pause” on their budget reconciliation plans. Manchin said he is worried about inflation and debt and said slowing down could give lawmakers more time to analyze the economic impacts of their spending plans. In a 50-50 Senate, and Republicans unified in opposition, Democrats can’t afford to lose Manchin.

Manchin is not alone in his concerns; a spokesperson for Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) recently reiterated that she will not support a package that costs $3.5 trillion.

Both Sinema and Manchin have urged the House to move the $1.2 trillion bipartisan bill separately.

Progressives like Sanders are pushing back on this rhetoric and have said in response that they will keep fighting to approve the smaller bipartisan infrastructure bill only if it’s paired with the reconciliation legislation.

“Rebuilding our crumbling physical infrastructure — roads, bridges, water systems — is important. Rebuilding our crumbling human infrastructure — health care, education, climate change — is more important. No infrastructure bill without the $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill,” tweeted Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT).

Budget Reconciliation Explained

Created by Congress in the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, reconciliation allows for expedited consideration of certain tax, spending and debt limit legislation. In the Senate, reconciliation bills are not subject to filibuster and the scope of amendments is limited, giving this process real advantages for enacting controversial budget and tax legislation with just 51 votes, rather than the usual threshold of 60 votes.

The purpose of the reconciliation process is to allow Congress to use an expedited procedure when considering legislation that would bring spending, revenue and debt limit laws into compliance with the current budgetary priorities. Prior to the passing of the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package signed earlier this year, 21 total budget reconciliation bills have been signed into law.

Any effort to pass further legislation with a simple majority will be considerably more difficult than it was with the stimulus package, which cleared both chambers and became law in less than three months.

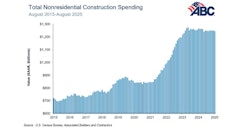

The Democratic deadlines over voting on the infrastructure package are set to collide with an end-of-the-month deadline to fund the government.

The House has voted 220 to 212 to consider the Senate-passed Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) no later than Sept. 27 with funding for critical programs like the Highway Trust Fund expiring September 30th.

Are We Facing Another Continuing Resolution?

Congress has until Oct. 1 to pass government funding bills to prevent a shutdown. While the House has passed nine of the fiscal 2022 government funding bills, The Hill has reported that the Senate has passed none. Senate Republicans have warned they won’t help pass the full-year bills without a deal on top-line spending numbers, an equal increase in defense and nondefense funding and an agreement to avoid politically controversial policy riders.

Instead, lawmakers are likely to use a continuing resolution, a short-term bill that continues current funding levels, into late November or December to keep the government running.

The continuing resolution could also be an attempted vehicle for raising the debt ceiling, which would effectively dare Republicans to either support a debt hike or risk a government shutdown. The Treasury Department is currently using so-called extraordinary measures to keep the country solvent but is expected to hit a wall sometime this fall.

Republicans have warned that they won’t help raise the debt ceiling, either on its own or if it's attached to something, because Democrats are planning to sidestep them to try to pass their $3.5 trillion plan. Democrats need at least 10 GOP votes in order to increase the nation’s borrowing limit. But 46 GOP senators signed a letter late last month vowing to oppose it, writing that “this is a problem created by Democrat spending. Democrats will have to accept sole responsibility for facilitating it.”

Democrats could raise the debt ceiling on their own as part of the $3.5 trillion spending package. But they left it out of their budget instructions, arguing that it should be bipartisan.