By Marc Scribner, senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute

The U.S. Interstate Highway System is the backbone of American commerce and personal travel. Funded on a pay-as-you-go basis largely through federal excise taxes on motor fuel, today it accounts for 25% of total vehicle-miles traveled despite accounting for just 2.5% of total road network lane-miles. Yet, much of the Interstate system, construction of which began in the 1950s, is nearing the end of its functional life, along with the infrastructure of other surface transportation modes. Over the next two decades, trillions of dollars of investment will be needed to rehabilitate and in some cases rebuild this infrastructure, according to some estimates.

Since 2008, Congress has bailed out the federal Highway Trust Fund to the tune of $140 billion as motor fuel tax receipts have stagnated while spending has continued to increase. In addition to the revenue-outlay imbalance at the federal level, outdated federal restrictions on highway tolling have denied to states opportunities to tailor transportation policy and funding to fit their residents’ needs. This status quo is not sustainable.

In recent years, there have been calls to increase federal motor fuel excise tax rates in order to address what many have called an infrastructure crisis. To be sure, there are very real infrastructure needs in the United States, but they are not uniform across infrastructure asset classes and are not primarily the result of a lack of federal funding. A more nuanced, targeted approach is needed to better address these challenges.

To tackle these challenges, Congress should focus on alternatives to the status quo that could more efficiently target infrastructure investments and increase the returns on those investments. Such an approach would benefit the public—taxpayers, infrastructure users, and consumers. This would involve reassessing the federal role in the provision of transportation infrastructure, examining alternatives to existing user taxes, and removing government barriers to investment.

Specifically, Congress should:

- Eliminate federal spending outside of highway freight corridors or at the very least allow federal capital funding to be redirected toward operations and maintenance activities;

- Establish a mileage-based user fee pilot program to examine a shift away from motor fuel user taxes;

- Eliminate federal prohibitions on states tolling their own Interstate segments;

- Eliminate the private activity bond lifetime volume cap and expand project eligibility;

- Eliminate procurement, labor, and environmental rules that unnecessarily increase costs and delay project delivery.

An untenable status quo

Contrary to a common narrative, infrastructure does not face a broad immediate crisis in the U.S. Private infrastructure owned and managed by freight rail and telecommunications firms is generally of high quality and is improving either without or with minimal taxpayer support. Public highway infrastructure is also of medium quality—although there is large variation across the states—and modestly improving, with the number of structurally deficient bridges and pavement roughness of the National Highway System seeing steady declines over the last three decades, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. U.S. DOT estimated transit networks' maintenance backlog was nearly $90 billion in 2015 and expect it to grow. Failure of routine maintenance by state and local governments also allows airports, urban surface streets, and water and wastewater networks to decay.

U.S. DOT estimated transit networks' maintenance backlog was nearly $90 billion in 2015 and expect it to grow. Failure of routine maintenance by state and local governments also allows airports, urban surface streets, and water and wastewater networks to decay.

We do see public infrastructure problems concentrated in America’s cities. The U.S. Department of Transportation estimated transit networks faced a maintenance backlog of nearly $90 billion in 2015 and is expected to continue growing. The failure of state and local governments to carry out routine maintenance following initial construction has also led to decay of airports, urban surface streets, and water and wastewater networks. Deferring routine maintenance not only leads to lower quality infrastructure, but increases the future costs of restoring infrastructure to a state of good repair.

Population growth has greatly outpaced expansion of U.S. highway lane-miles. This plus poor management practices have resulted in crippling peak-hour traffic congestion in urban areas throughout the U.S. In 2015, the Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI) estimated that traffic congestion resulted in 3 billion gallons of wasted fuel and nearly 7 billion hours in wasted time per year. The nationwide cost was estimated to be $160 billion, or $960 per rush-hour commuter. This represented a 140% increase in commuting delay and wasted fuel congestion costs since 1982.

But the TTI congestion analysis looks only at commuting motorists’ travel time delay and wasted fuel costs. When considering the costs associated with productivity losses, unreliability losses, truck cargo delays, and safety and environmental costs, the total annual economic cost of congestion was estimated by the chief economist of the U.S. Department of Transportation to be more than double the TTI estimate.

Study Attributes 2,200 Deaths, $18 Billion Cost to Traffic

Further complicating matters is the heavy reliance on fuel excise taxes to fund the majority of federally aided infrastructure projects. Inflation has steadily eroded the purchasing power of motor fuel tax revenue, where tax rates were last raised in 1993. Increasing fuel efficiency and electrification of the vehicle fleet has led to declining revenue per vehicle-mile traveled. In turn, this has increased the regressive nature of motor fuel taxes, as lower-income Americans tend to drive older, less fuel efficient vehicles. With Interstate Highway System repair needs estimated to be more than $1 trillion over the next two decades, something must be done to ensure U.S. transportation infrastructure can continue to be a productive force for on the U.S. economy.

Reassessing the feds' infrastructure role

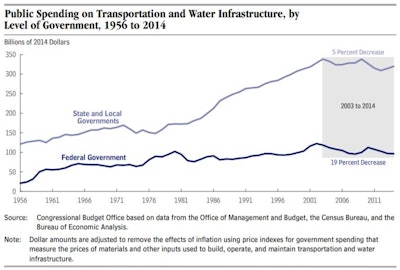

The federal role in transportation infrastructure spending is primarily in the form  Beginning in 2003, construction raw materials prices increased faster than prices of other goods. Inflation-adjusted public infrastructure spending has declined about 9% since 2003, with a 5% decrease in state spending and a 19% drop in federal funding.Congressional Budget Office

Beginning in 2003, construction raw materials prices increased faster than prices of other goods. Inflation-adjusted public infrastructure spending has declined about 9% since 2003, with a 5% decrease in state spending and a 19% drop in federal funding.Congressional Budget Office

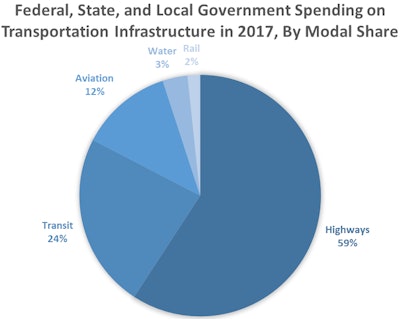

CBO Whitepaper: Public Spending on Transportation and Water Infrastructure, 1956 to 2014

The federal government is responsible for approximately one-quarter of total public spending on highways and mass transit. State and local governments fund the rest. Aviation infrastructure spending is more evenly split between federal and state and local governments, with the federal share of aviation infrastructure spending being concentrated in the Federal Aviation Administration’s air traffic control system. According to the Congressional Budget Office, federal, state, and local governments spent a combined $299 billion on highway ($177 billion), mass transit ($70 billion), aviation ($37 billion), water ($10 billion), and intercity passenger rail ($5 billion) infrastructure in 2017.

As networks have matured, the continued lopsided federal role in capital spending has created perverse incentives for state and local governments to seek new-build projects rather than maintain what has already been built. This, combined with the fact that states and localities are mainly responsible for maintenance of built infrastructure long after the feds have left town, has led to significant over-expansion of mass transit systems that state and local government owners cannot afford to maintain.

To put this in perspective, just 5% of American workers aged 16 years and older commuted to work via mass transit in 2017 according to Census Bureau data. In contrast, 76% of workers drove alone and 9% carpooled. Despite this, in 2017, mass transit received 28% of total federal, state, and local surface transportation funding—more than five times its commuting mode share and 11 times mass transit’s share of total commuting and non-commuting trips.

While the largely user-supported highway system moves more than $10 trillion worth of freight every year in the U.S., mass transit moves zero freight while enjoying substantial diversions of revenue collected from road users. The 25% of federal highway user tax revenue diverted to non-highway projects has put the long-term solvency of the Highway Trust Fund in jeopardy.

What is the Highway Trust Fund & Why is it Going Broke?

A rationalized federal role in transportation infrastructure would focus on projects with true national significance that facilitate interstate commerce and international trade: freight movements. The Constitution explicitly recognizes these roles as federal functions. Mass transit systems that exist primarily to move local commuters, and do not move any freight, cannot be appropriately labeled deemed to be nationally significant. This is not to say that New York City’s subway system is not vitally important to New Yorkers, only that construction and maintenance of mass transit systems is more appropriately addressed by individual metropolitan areas who best know their particular transportation and land-use needs.

Short of eliminating federal funding for non-nationally significant projects, Congress could de-emphasize the federal role in capital spending and allow for more of those funds to be spent on maintenance activities under a “fix it first” strategy.

Alternatives to existing user taxes

A top priority in federal transportation infrastructure policy should be to preserve and strengthen the longstanding users-pay/users-benefit fiscal principle. This approach offers several advantages over general revenue funding:

- Fairness: Highway users benefit from the improvements their user taxes generate.

- Proportionality: Users who drive more pay more.

- Funding predictability: Highway use and highway user revenues do not fluctuate wildly in the short-run.

- Signaling investment: Because revenue roughly tracks use, the mechanism provides policy makers with an important signal as to how much infrastructure investment is needed to maintain a desired level of efficiency.

The approach was adopted under the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 and the accompanying Highway Revenue Act, which established the Highway Trust Fund. Excise taxes on gasoline and diesel account for nearly 90% of total Highway Trust Fund revenue. These are collected from fuel producers and importers, who then pass most of the tax burden onto consumers. The current rates of 18.4 cents per gallon of gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon of diesel were last raised in 1993.

At a time when toll collection required stopping at toll booths and resulted in high administrative costs and traffic congestion, per-gallon taxation of fuel served as an appropriate user tax when road users with similarly weighted vehicles consumed roughly the same amount of fuel per mile driven. However, fuel consumption is becoming an increasingly poor proxy for highway use. As the vehicle fleet continues to achieve improved fuel economy and gradually electrifies or otherwise moves away from fossil fuels, an alternative to motor fuel taxes as the primary highway revenue source is needed.

Removing barriers to transportation investment

Unfortunately, the aforementioned alternatives to motor fuel taxation are greatly constrained by outdated federal law. Under current law, tolling is generally prohibited on the federally aided highway system. In recent decades, Congress has enacted several exceptions to this rule but limited exemptions have led to less than 5% of U.S. highway miles being tolled. Many highway users, especially the trucking industry, have long opposed toll roads. Road users do have some legitimate concerns that should be addressed if Congress were to eliminate the Section 301 general prohibition on tolls. Transportation policy scholar Robert W. Poole, Jr., has developed a concept he calls “value-added tolling.” He argues that Congress should permit tolling if the projects adhere to five principles:

- Begin tolling only after major improvements are completed;

- Prohibit toll revenue diversion to projects outside the facility or system were they are collected;

- Toll rates should only be high enough to cover initial construction or rehabilitation, maintenance and operations, and needed improvements;

- Motor fuel taxpayers should be reimbursed for the taxes they paid while using toll roads; and

- Provide a better level of service on the facility after tolling is imposed.

Protections from toll road operator predation should accompany any liberalization of federal tolling restrictions. Value-added tolling provides a workable framework. If these statutory restrictions were to be lifted, Congress could unleash another alternative to government spending on transportation infrastructure: private investment.

In countries as varied as Australia, France, China and Chile, public-private partnerships (P3s) have played major roles in the provision and management of transportation infrastructure. Concession agreements under which the concessionaire designs, builds, finances, operates, and maintains the project over the long term have successfully reduced project costs, shifted costs and risks away from taxpayers and onto private investors and users, and delivered projects in a more timely fashion. In the U.S., several states have enacted robust P3 legislation and have entered into long-term leases with private concessionaires to build, modernize, and/or manage public-purpose tolled highways. This has resulted in road users getting better infrastructure and taxpayers saving billions of dollars.

Reason Foundation: Pros and Cons of P3s

These P3 toll roads rely on a mix of equity and debt financing. Private activity bonds (PABs) play a key role, with toll revenue used to service this debt. PABs are tax exempt like traditional municipal bonds, leveling the playing field between the public and private sectors in financing infrastructure. Unfortunately, Congress created a national aggregate volume cap on PABs of $15 billion for surface transportation projects. According to the latest data from the U.S. Department of Transportation, more than two-thirds of that $15 billion has already been issued or allocated. If Congress wants to free the states and private sector in delivering better infrastructure value to the traveling public, this cap should be greatly increased or eliminated.

Should the Asphalt Industry Consider More P3 Projects?

In addition, federal, state, and local procurement policies, labor requirements, environmental permitting rules, and a lack of adequate life-cycle cost accounting all serve to substantially increase the cost of building and maintaining public-purpose infrastructure. Recent efforts from Congress and the administration on permitting reform—especially the ongoing “one federal decision” implementation—are promising, but much more reform is necessary.

Conclusion

If there is an infrastructure crisis in the U.S., it is certainly not uniform across asset classes or geography. Any policy response must take into account these differences in order to effectively target problems where they exist.

Reforms should focus on maximizing returns on infrastructure investment, not maximizing the number of temporary jobs created in the initial construction of new infrastructure. As Harvard University urban economist Edward L. Glaeser recently noted, “Treating transportation infrastructure as yet another public-works program ensures the mediocrity that we see all around us.”

Across this landscape, current federal law perversely reduces surface transportation infrastructure investment while increasing government spending and pressure on taxpayers. The reforms to federal surface transportation policy suggested above could unleash new investment and new practices to contain costs and deliver substantial benefits to infrastructure users without burdening Americans with additional federal taxes.

Marc Scribner is a senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI). CEI is a non-profit public policy organization based in Washington, D.C., dedicated to advancing the principles of limited government, free enterprise, and individual liberty. You can view the full report from CEI here.